Canadians

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Canada: 41,465,298 (Q4 2024)[1] Ethnic origins:[2][3]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| United States | 1,062,640[5] |

| Hong Kong | 300,000[5] |

| United Kingdom | 73,000[5] |

| France | 60,000[6] |

| Lebanon | 45,000[5] |

| United Arab Emirates | 40,000[7] |

| Italy | 30,000[8] |

| Pakistan | 30,000[9] |

| Australia | 27,289[5] |

| China | 19,990[5] |

| Germany | 15,750[10] |

| South Korea | 14,210[5] |

| Japan | 11,016[5] |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

Religions of Canada[11]

| |

Canadians (French: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being Canadian.

Canada is a multilingual and multicultural society home to people of groups of many different ethnic, religious, and national origins, with the majority of the population made up of Old World immigrants and their descendants. Following the initial period of French and then the much larger British colonization, different waves (or peaks) of immigration and settlement of non-indigenous peoples took place over the course of nearly two centuries and continue today. Elements of Indigenous, French, British, and more recent immigrant customs, languages, and religions have combined to form the culture of Canada, and thus a Canadian identity and Canadian values. Canada has also been strongly influenced by its linguistic, geographic, and economic neighbour—the United States.

Canadian independence from the United Kingdom grew gradually over the course of many years following the formation of the Canadian Confederation in 1867. The First and Second World Wars, in particular, gave rise to a desire among Canadians to have their country recognized as a fully-fledged, sovereign state, with a distinct citizenship. Legislative independence was established with the passage of the Statute of Westminster, 1931, the Canadian Citizenship Act, 1946, took effect on January 1, 1947, and full sovereignty was achieved with the patriation of the constitution in 1982. Canada's nationality law closely mirrored that of the United Kingdom. Legislation since the mid-20th century represents Canadians' commitment to multilateralism and socioeconomic development.

Term

The word Canadian originally applied, in its French form, Canadien, to the colonists residing in the northern part of New France[12]— in Quebec, and Ontario—during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. The French colonists in Maritime Canada (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island), were known as Acadians.

When Prince Edward (a son of King George III) addressed, in English and French, a group of rioters at a poll in Charlesbourg, Lower Canada (today Quebec), during the election of the Legislative Assembly in June 1792,[13] he stated, "I urge you to unanimity and concord. Let me hear no more of the odious distinction of English and French. You are all His Britannic Majesty's beloved Canadian subjects."[14] It was the first-known use of the term Canadian to mean both French and English settlers in the Canadas.[13][15]

Population

As of 2010, Canadians make up 0.5% of the world's total population,[16] having relied upon immigration for population growth and social development.[17] Approximately 41% of current Canadians are first- or second-generation immigrants,[18] and 20% of Canadian residents in the 2000s were not born in the country.[19] Statistics Canada projects that, by 2031, nearly one-half of Canadians above the age of 15 will be foreign-born or have one foreign-born parent.[20] Indigenous peoples, according to the 2016 Canadian census, numbered at 1,673,780 or 4.9% of the country's 35,151,728 population.[21]

Immigration

While the first contact with Europeans and Indigenous peoples in Canada had occurred a century or more before, the first group of permanent settlers were the French, who founded the New France settlements, in present-day Quebec and Ontario; and Acadia, in present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, during the early part of the 17th century.[22][23]

Approximately 100 Irish-born families would settle the Saint Lawrence Valley by 1700, assimilating into the Canadien population and culture.[24][25] During the 18th and 19th century; immigration westward (to the area known as Rupert's Land) was carried out by "Voyageurs"; French settlers working for the North West Company; and by British settlers (English and Scottish) representing the Hudson's Bay Company, coupled with independent entrepreneurial woodsman called coureur des bois.[26] This arrival of newcomers led to the creation of the Métis, an ethnic group of mixed European and First Nations parentage.[27]

In the wake of the British Conquest of New France in 1760 and the Expulsion of the Acadians, many families from the British colonies in New England moved over into Nova Scotia and other colonies in Canada, where the British made farmland available to British settlers on easy terms. More settlers arrived during and after the American Revolutionary War, when approximately 60,000 United Empire Loyalists fled to British North America, a large portion of whom settled in New Brunswick.[28] After the War of 1812, British (including British army regulars), Scottish, and Irish immigration was encouraged throughout Rupert's Land, Upper Canada and Lower Canada.[29]

Between 1815 and 1850, some 800,000 immigrants came to the colonies of British North America, mainly from the British Isles as part of the Great Migration of Canada.[30] These new arrivals included some Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots displaced by the Highland Clearances to Nova Scotia.[31] The Great Famine of Ireland of the 1840s significantly increased the pace of Irish immigration to Prince Edward Island and the Province of Canada, with over 35,000 distressed individuals landing in Toronto in 1847 and 1848.[32][33] Descendants of Francophone and Anglophone northern Europeans who arrived in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries are often referred to as Old Stock Canadians.[34][35]

Beginning in the late 1850s, the immigration of Chinese into the Colony of Vancouver Island and Colony of British Columbia peaked with the onset of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.[36] The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 eventually placed a head tax on all Chinese immigrants, in hopes of discouraging Chinese immigration after completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[37] Additionally, growing South Asian immigration into British Columbia during the early 1900s[38] led to the continuous journey regulation act of 1908 which indirectly halted Indian immigration to Canada, as later evidenced by the infamous 1914 Komagata Maru incident.

| Rank | Country | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 127,795 | 31.5 | |

| 2 | 30,970 | 7.6 | |

| 3 | 17,990 | 4.4 | |

| 4 | 15,580 | 3.8 | |

| 5 | 12,685 | 3.1 | |

| 6 | 11,930 | 2.9 | |

| 7 | 11,420 | 2.8 | |

| 8 | 11,285 | 2.8 | |

| 9 | 8,550 | 2.1 | |

| 10 | 8,410 | 2.1 | |

| Top 10 Total | 256,615 | 63.3 | |

| Other | 148,715 | 36.7 | |

| Total | 405,330 | 100 |

The population of Canada has consistently risen, doubling approximately every 40 years, since the establishment of the Canadian Confederation in 1867.[40] In the mid-to-late 19th century, Canada had a policy of assisting immigrants from Europe, including an estimated 100,000 unwanted "Home Children" from Britain.[41] Block settlement communities were established throughout Western Canada between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some were planned and others were spontaneously created by the settlers themselves.[42] Canada received mainly European immigrants, predominantly Italians, Germans, Scandinavians, Dutch, Poles, and Ukrainians.[43] Legislative restrictions on immigration (such as the continuous journey regulation and Chinese Immigration Act, 1923) that had favoured British and other European immigrants were amended in the 1960s, opening the doors to immigrants from all parts of the world.[44] While the 1950s had still seen high levels of immigration by Europeans, by the 1970s immigrants were increasingly Chinese, Indian, Vietnamese, Jamaican, and Haitian.[45] During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Canada received many American Vietnam War draft dissenters.[46] Throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, Canada's growing Pacific trade brought with it a large influx of South Asians, who tended to settle in British Columbia.[47] Immigrants of all backgrounds tend to settle in the major urban centres.[48][49] The Canadian public, as well as the major political parties, are tolerant of immigrants.[50]

The majority of illegal immigrants come from the southern provinces of the People's Republic of China, with Asia as a whole, Eastern Europe, Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East.[51] Estimates of numbers of illegal immigrants range between 35,000 and 120,000.[52]

Citizenship and diaspora

Canadian citizenship is typically obtained by birth in Canada or by birth or adoption abroad when at least one biological parent or adoptive parent is a Canadian citizen who was born in Canada or naturalized in Canada (and did not receive citizenship by being born outside of Canada to a Canadian citizen).[53] It can also be granted to a permanent resident who lives in Canada for three out of four years and meets specific requirements.[54] Canada established its own nationality law in 1946, with the enactment of the Canadian Citizenship Act which took effect on January 1, 1947.[55] The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada in 2001 as Bill C-11, which replaced the Immigration Act, 1976 as the primary federal legislation regulating immigration.[56] Prior to the conferring of legal status on Canadian citizenship, Canada's naturalization laws consisted of a multitude of Acts beginning with the Immigration Act of 1910.[57]

According to Citizenship and Immigration Canada, there are three main classifications for immigrants: family class (persons closely related to Canadian residents), economic class (admitted on the basis of a point system that accounts for age, health and labour-market skills required for cost effectively inducting the immigrants into Canada's labour market) and refugee class (those seeking protection by applying to remain in the country by way of the Canadian immigration and refugee law).[58] In 2008, there were 65,567 immigrants in the family class, 21,860 refugees, and 149,072 economic immigrants amongst the 247,243 total immigrants to the country.[18] Canada resettles over one in 10 of the world's refugees[59] and has one of the highest per-capita immigration rates in the world.[60]

As of a 2010 report by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, there were 2.8 million Canadian citizens abroad.[61] This represents about 8% of the total Canadian population. Of those living abroad, the United States, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, China, Lebanon, United Arab Emirates, and Australia have the largest Canadian diaspora. Canadians in the United States constitute the greatest single expatriate community at over 1 million in 2009, representing 35.8% of all Canadians abroad.[62] Under current Canadian law, Canada does not restrict dual citizenship, but Passport Canada encourages its citizens to travel abroad on their Canadian passport so that they can access Canadian consular services.[63]

Ethnic ancestry

English Irish Scottish French German Chinese Indian Ukrainian | Métis Acadian Mennonite Inuit Cree Ojibway Dene Heiltsuk |

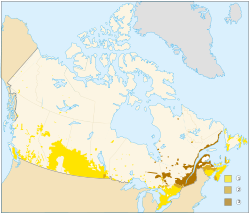

According to the 2021 Canadian census, over 450 "ethnic or cultural origins" were self-reported by Canadians.[4] The major panethnic origin groups in Canada are: European (52.5%), North American (22.9%), Asian (19.3%), North American Indigenous (6.1%), African (3.8%), Latin, Central and South American (2.5%), Caribbean (2.1%), Oceanian (0.3%), and Other (6%).[4][64] Statistics Canada reports that 35.5% of the population reported multiple ethnic origins, thus the overall total is greater than 100%.[4][d]

The country's ten largest self-reported specific ethnic or cultural origins in 2021 were Canadian[c] (accounting for 15.6 percent of the population), followed by English (14.7 percent), Irish (12.1 percent), Scottish (12.1 percent), French (11.0 percent), German (8.1 percent),Indian (5.1 percent),[e] Chinese (4.7 percent), Italian (4.3 percent), and Ukrainian (3.5 percent).[68][64]

Of the 36.3 million people enumerated in 2021 approximately 24.5 million reported being "white", representing 67.4 percent of the population.[69][70] The indigenous population representing 5 percent or 1.8 million individuals, grew by 9.4 percent compared to the non-Indigenous population, which grew by 5.3 percent from 2016 to 2021.[71] One out of every four Canadians or 26.5 percent of the population belonged to a non-White and non-Indigenous visible minority,[70][f] the largest of which in 2021 were South Asian (2.6 million people; 7.1 percent), Chinese (1.7 million; 4.7 percent) and Black (1.5 million; 4.3 percent).[69]

Between 2011 and 2016, the visible minority population rose by 18.4 percent.[73] In 1961, less than two percent of Canada's population (about 300,000 people) were members of visible minority groups.[74] The 2021 Census indicated that 8.3 million people, or almost one-quarter (23.0 percent) of the population reported themselves as being or having been a landed immigrant or permanent resident in Canada—above the 1921 Census previous record of 22.3 percent.[75] In 2021 India, China, and the Philippines were the top three countries of origin for immigrants moving to Canada.[76]

Culture

Canadian culture is primarily a Western culture, with influences by First Nations and other cultures. It is a product of its ethnicities, languages, religions, political, and legal system(s). Canada has been shaped by waves of migration that have combined to form a unique blend of art, cuisine, literature, humour, and music.[77] Today, Canada has a diverse makeup of nationalities and constitutional protection for policies that promote multiculturalism rather than cultural assimilation.[78] In Quebec, cultural identity is strong, and many French-speaking commentators speak of a Quebec culture distinct from English Canadian culture.[79] However, as a whole, Canada is a cultural mosaic: a collection of several regional, indigenous, and ethnic subcultures.[80][81]

Canadian government policies such as official bilingualism; publicly funded health care; higher and more progressive taxation; outlawing capital punishment; strong efforts to eliminate poverty; strict gun control; the legalizing of same-sex marriage, pregnancy terminations, euthanasia and cannabis are social indicators of Canada's political and cultural values.[82][83] American media and entertainment are popular, if not dominant, in English Canada; conversely, many Canadian cultural products and entertainers are successful in the United States and worldwide.[84] The Government of Canada has also influenced culture with programs, laws, and institutions. It has created Crown corporations to promote Canadian culture through media, and has also tried to protect Canadian culture by setting legal minimums on Canadian content.[85]

Canadian culture has historically been influenced by European culture and traditions, especially British and French, and by its own indigenous cultures. Most of Canada's territory was inhabited and developed later than other European colonies in the Americas, with the result that themes and symbols of pioneers, trappers, and traders were important in the early development of the Canadian identity.[86] First Nations played a critical part in the development of European colonies in Canada, particularly for their role in assisting exploration of the continent during the North American fur trade.[87] The British conquest of New France in the mid-1700s brought a large Francophone population under British Imperial rule, creating a need for compromise and accommodation.[88] The new British rulers left alone much of the religious, political, and social culture of the French-speaking habitants, guaranteeing through the Quebec Act of 1774 the right of the Canadiens to practise the Catholic faith and to use French civil law (now Quebec law).[89]

The Constitution Act, 1867 was designed to meet the growing calls of Canadians for autonomy from British rule, while avoiding the overly strong decentralization that contributed to the Civil War in the United States.[90] The compromises made by the Fathers of Confederation set Canadians on a path to bilingualism, and this in turn contributed to an acceptance of diversity.[91][92]

The Canadian Armed Forces and overall civilian participation in the First World War and Second World War helped to foster Canadian nationalism,[93][94] however, in 1917 and 1944, conscription crisis' highlighted the considerable rift along ethnic lines between Anglophones and Francophones.[95] As a result of the First and Second World Wars, the Government of Canada became more assertive and less deferential to British authority.[96] With the gradual loosening of political ties to the United Kingdom and the modernization of Canadian immigration policies, 20th-century immigrants with African, Caribbean and Asian nationalities have added to the Canadian identity and its culture.[97] The multiple-origins immigration pattern continues today, with the arrival of large numbers of immigrants from non-British or non-French backgrounds.[98]

Multiculturalism in Canada was adopted as the official policy of the government during the premiership of Pierre Trudeau in the 1970s and 1980s.[99] The Canadian government has often been described as the instigator of multicultural ideology, because of its public emphasis on the social importance of immigration.[100] Multiculturalism is administered by the Department of Citizenship and Immigration and reflected in the law through the Canadian Multiculturalism Act[101] and section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[102]

Values

Canadian values are the perceived commonly shared ethical and human values of Canadians.[103] Canadians generally exhibit pride in equality before the law, fairness, social justice, freedom, and respect for others;[104] while often making personal decisions based on self interests rather than a collective Canadian identity.[105] Tolerance and sensitivity hold significant importance in Canada's multicultural society, as does politeness.[105][106] A vast majority of Canadians shared the values of human rights, respect for the law and gender equality.[107][106] Historian Ian MacKay associates Canadian values with egalitarianism, equalitarianism and peacefulness.[108]

Numerous scholars have tried to identify, measure and compare Canadian values with other countries, especially the United States.[109][110] However, there are critics who say that such a task is practically impossible.[111] Political scientist Denis Stairs connects values with Canadian nationalism, noting Canadians feel they hold special, virtuous values.[112] Canadians identify with the country's institutions of health care, military peacekeeping, the national park system and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[113][104]Identity

Canadian identity refers to the unique culture, characteristics and condition of being Canadian, as well as the many symbols and expressions that set Canada and Canadians apart from other peoples and cultures of the world. Changes in demographics, history, and social interactions have led to alterations in the Canadian identity over time. This identity is not fixed; as Canadian values evolve they impact Canadians' social integration, civic engagement, and connections with one another.[114]

Despite efforts, Canadians have never been able to agree on a cohesive image of their country. The notions of Canadian identity have oscillated between oneness and plurality, emphasizing either a single Canada or multiple nations. Modern Canadian identity is characterized by both unity and plurality. This pluralist approach is to find common ground and evaluate identity through regional, ethnic (including immigrants), religious and political debate.[115] Richard Gwyn has suggested that "tolerance" has replaced "loyalty" as the touchstone of Canadian identity.[116] Canadian Prime Ministers and journalists have defined the country as a postnational state.[117][118][119]Religion

Religion in Canada encompasses a wide range of beliefs and customs that historically has been dominated by Christianity.[121][122] The constitution of Canada refers to 'God', however Canada has no official church and the government is officially committed to religious pluralism.[123] Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing individuals to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.[124] Rates of religious adherence have steadily decreased since the 1960s.[122] After having once been central and integral to Canadian culture and daily life,[125] Canada has become a post-Christian state.[126][127][128] Although the majority of Canadians consider religion to be unimportant in their daily lives,[129] they still believe in God.[130] The practice of religion is generally considered a private matter throughout society and the state.[131]

Before the European colonization, a wide diversity of Native religions and belief systems of the Indigenous peoples in Canada were largely animistic or shamanistic.[132][133][134][135] The French colonization beginning in the 16th century established a Catholic French population in New France.[136] During the colonial period, the French settled along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, specifically Latin Church Catholics, including a number of Jesuits dedicated to converting indigenous peoples.[137] These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with forced integration through state-funded boarding schools run by both Catholics and Protestants that attempted to assimilate Indigenous children.[138]

British colonization brought waves of Anglicans and other Protestants to Upper Canada, now Ontario.[139] The settlement of the West brought significant Eastern Orthodox immigrants from Eastern Europe and Mormon and Pentecostal immigrants from the United States.[140] The Jewish, Islamic, Jains, Sikh, Hindu, and Buddhist communities—although small—are as old as the nation itself.[141]Symbols

Themes of nature, pioneers, trappers, and traders played an important part in the early development of Canadian symbolism.[142] Modern symbols emphasize the country's geography, cold climate, lifestyles, and the Canadianization of traditional European and Indigenous symbols.[143] The use of the maple leaf as a Canadian symbol dates to the early 18th century. The maple leaf is depicted on Canada's current and previous flags and on the Arms of Canada.[144] Canada's official tartan, known as the "maple leaf tartan", reflects the colours of the maple leaf through the seasons—green in the spring, gold in the early autumn, red at the first frost, and brown after falling.[145] The Arms of Canada are closely modelled after those of the United Kingdom, with French and distinctive Canadian elements replacing or added to those derived from the British version.[146]

Other prominent symbols include the national motto, "A mari usque ad mare" ("From Sea to Sea"),[147] the sports of ice hockey and lacrosse, the beaver, Canada goose, common loon, Canadian horse, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Canadian Rockies,[144] and, more recently, the totem pole and Inuksuk.[148] Canadian beer, maple syrup, tuques, canoes, nanaimo bars, butter tarts, and poutine are defined as uniquely Canadian.[149] Canadian coins feature many of these symbols: the loon on the $1 coin, the Arms of Canada on the 50¢ piece, and the beaver on the nickel.[150] An image of the monarch appears on $20 bank notes and the obverse of coins.[150]Languages

A multitude of languages are used by Canadians, with English and French (the official languages) being the mother tongues of approximately 56% and 21% of Canadians, respectively.[152] As of the 2016 Census, just over 7.3 million Canadians listed a non-official language as their mother tongue. Some of the most common non-official first languages include Chinese (1,227,680 first-language speakers), Punjabi (501,680), Spanish (458,850), Tagalog (431,385), Arabic (419,895), German (384,040), and Italian (375,645).[152] Less than one percent of Canadians (just over 250,000 individuals) can speak an indigenous language. About half this number (129,865) reported using an indigenous language on a daily basis.[153] Additionally, Canadians speak several sign languages; the number of speakers is unknown of the most spoken ones, American Sign Language (ASL) and Quebec Sign Language (LSQ),[154] as it is of Maritime Sign Language and Plains Sign Talk.[155] There are only 47 speakers of the Inuit sign language Inuktitut.[156]

English and French are recognized by the Constitution of Canada as official languages.[157] All federal government laws are thus enacted in both English and French, with government services available in both languages.[157] Two of Canada's territories give official status to indigenous languages. In Nunavut, Inuktitut, and Inuinnaqtun are official languages, alongside the national languages of English and French, and Inuktitut is a common vehicular language in territorial government.[158] In the Northwest Territories, the Official Languages Act declares that there are eleven different languages: Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwich'in, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, and Tłįchǫ.[159] Multicultural media are widely accessible across the country and offer specialty television channels, newspapers, and other publications in many minority languages.[160]

In Canada, as elsewhere in the world of European colonies, the frontier of European exploration and settlement tended to be a linguistically diverse and fluid place, as cultures using different languages met and interacted. The need for a common means of communication between the indigenous inhabitants and new arrivals for the purposes of trade, and (in some cases) intermarriage, led to the development of mixed languages.[161] Languages like Michif, Chinook Jargon, and Bungi creole tended to be highly localized and were often spoken by only a small number of individuals who were frequently capable of speaking another language.[162] Plains Sign Talk—which functioned originally as a trade language used to communicate internationally and across linguistic borders—reached across Canada, the United States, and into Mexico.[163]

See also

- Canuck

- List of Canadians

- Persons of National Historic Significance

- List of prime ministers of Canada

Notes

- ^ Catholic 29.9%, United Church 3.3%, Anglican 3.1%, Orthodox 1.7%, Baptist 1.2%, Pentecostal 1.1%, Lutheran 0.9%, Presbyterian 0.8%, Anabaptist 0.4%, Jehovah's Witness 0.4%, Methodist 0.3%, Latter Day Saints 0.2%, Reformed 0.2%, other Christian 9.7%.

- ^ Officially, the People's Republic of China. Excludes Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (listed separately).

- ^ a b All citizens of Canada are classified as "Canadians" as defined by Canada's nationality laws. "Canadian" as an ethnic group has since 1996 been added to census questionnaires for possible ancestral origin or descent. "Canadian" was included as an example on the English questionnaire and "Canadien" as an example on the French questionnaire.[65] The majority of respondents to this selection are from the eastern part of the country that was first settled. Respondents generally are visibly European (Anglophones and Francophones) and no longer self-identify with their ethnic ancestral origins. This response is attributed to a multitude of reasons such as generational distance from ancestral lineage.[66][67]

- ^ The 2021 census on ethnic or cultural origins, Statistics Canada states: "Given the fluid nature of this concept and the changes made to this question, 2021 Census data on ethnic or cultural origins are not comparable to data from previous censuses and should not be used to measure the growth or decline of the various groups associated with these origins".[4]

- ^ Statistic includes all persons with ethnic or cultural origin responses with ancestry to the nation of India, including "Anglo-Indian" (3,340), "Bengali" (26,675), "Goan" (9,700), "Gujarati" (36,970), "Indian" (1,347,715), "Jatt" (22,785), "Kashmiri" (6,165), "Maharashtrian" (4,125), "Malayali" (12,490), "Punjabi" (279,950), "Tamil" (102,170), and "Telugu" (6,670)".[68]

- ^ Indigenous peoples are not considered a visible minority in Statistics Canada calculations. Visible minorities are defined by Statistics Canada as "persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour".[72]

References

- ^ Statistics Canada (September 29, 2021). "Population estimates, quarterly". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

In 2021, just over 25 million people reported being White in the census, representing close to 70% of the total Canadian population. The vast majority reported being White only, while 2.4% also reported one or more other racialized groups.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Visible minority and population group by generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Canadians Abroad: Canada's Global Asset" (PDF). Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2011. p. 12. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Relations bilatérales du Canada et France". France Diplomatie : : Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "Canada may limit services for dual citizens". Gulf News. January 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b "Global Migration Map: Origins and Destinations, 1990–2017". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. February 28, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Hasan, Shazia (August 20, 2019). "HC highlights growing ties between Canada, Pakistan". Dawn. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

Meanwhile, there are some 30,000 to 50,000 Canadians in Pakistan

- ^ "Ausländeranteil in Deutschland bis 2018". Statista.

- ^ a b "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022.

- ^ Daily Life in New France, Canadian History Project, retrieved March 15, 2023

- ^ a b Bousfuield, Arthur; Toffoli, Garry (2010). Royal Tours 1786–2010: Home to Canada. Dundurn Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4597-1165-5.

- ^ Harris, Caroline (February 3, 2022), "Royals Who Lived in Canada", The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, retrieved March 13, 2023

- ^ Tidridge, Nathan (2013). Prince Edward, Duke of Kent: Father of the Canadian Crown. Dundurn Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-4597-0790-0.

- ^ "Environment – Greenhouse Gases (Greenhouse Gas Emissions per Person)". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Cornelius et al. 2004, p. 100.

- ^ a b "Canada – Permanent residents by gender and category, 1984 to 2008". Facts and figures 2008 – Immigration overview: Permanent and temporary residents. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. August 25, 2009. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ Bybee & McCrae 2009, p. 92.

- ^ "Projections of the Diversity of the Canadian Population". Statistics Canada. March 9, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ "Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis, and Inuit". Statistics Canada. 2012.

- ^ Hudson 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Griffiths 2005, p. 4.

- ^ McGowan 1999.

- ^ Magocsi 1999, p. 736ff.

- ^ Standford 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Borrows 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Murrin et al. 2007, p. 172.

- ^ Feltes 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Harland-Jacobs 2007, p. 177.

- ^ Campey 2008, p. 122.

- ^ McGowan 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Elliott 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Boberg, Charles (2010). The English Language in Canada: Status, History, and Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 9781139491440.

- ^ Chown, Marco; Otis, Daniel (September 18, 2015). "Who are 'old stock Canadians'? The Star asked some people with deep roots in Canada what they thought of Conservative Leader Stephen Harper's controversial phrase". Toronto. Toronto Star. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ^ Hall & Hwang 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Huang 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Singh, Hira, p. 94[permanent dead link] (Archive).

- ^ "Permanent Residents – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Admissions of Permanent Residents by Country of Citizenship". Statistics Canada. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "Canadians in Context – Population Size and Growth". Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Hobbs, MacKechnie & Lavalette 1999, p. 33.

- ^ Martens 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Day 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Ksenych & Liu 2001, p. 407.

- ^ "Immigration Policy in the 1970s". Canadian Heritage (Multicultural Canada). 2004. Archived from the original on November 5, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- ^ Kusch 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Agnew 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Wilkinson 1980, p. 200.

- ^ Good 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Hollifield, Martin & Orrenius 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Schneider 2009, p. 367.

- ^ "Canadians want illegal immigrants deported: poll". Ottawa Citizen. CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc. October 20, 2007. Archived from the original on October 20, 2010. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "Am I Canadian?". Government of Canada Canada. 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Citizenship Act (R.S., 1985, c. C-29)". Department of Justice Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on January 6, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Citizenship Act and current issues -BP-445E". Government of Canada – Law and Government Division. 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Sinha, Jay; Young, Margaret (January 31, 2002). "Bill C-11 : Immigration and Refugee Protection Act". Law and Government Division, Government of Canada. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Bloemraad 2006, p. 269.

- ^ "Canadian immigration". Canada Immigration Visa. 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ "Canada's Generous Program for Refugee Resettlement Is Undermined by Human Smugglers Who Abuse Canada's Immigration System". Public Safety Canada. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ Zimmerman 2008, p. 51.

- ^ DeVoretz 2011.

- ^ "United States Total Canadian Population: Fact Sheet" (PDF). Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ Gray 2010, p. 302.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ Simon, Patrick; Piché, Victor (2013). Accounting for Ethnic and Racial Diversity: The Challenge of Enumeration. Routledge. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-317-98108-4.

- ^ Bezanson, Kate; Webber, Michelle (2016). Rethinking Society in the 21st Century (4th ed.). Canadian Scholars' Press. pp. 455–456. ISBN 978-1-55130-936-1.

- ^ Edmonston, Barry; Fong, Eric (2011). The Changing Canadian Population. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 294–296. ISBN 978-0-7735-3793-4.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table Canada [Country] Total – Ethnic or cultural origin for the population in private households – 25% sample data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Daily — The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (October 26, 2022). "Visible minority and population group by generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Daily — Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed". Statistics Canada. September 21, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "Classification of visible minority". Statistics Canada. July 25, 2008. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ Pendakur, Krishna. "Visible Minorities and Aboriginal Peoples in Vancouver's Labour Market". Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Daily — Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ "2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration". Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. March 15, 2022.

- ^ Kalman 2009, pp. 4–7.

- ^ DeRocco & Chabot 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Franklin & Baun 1995, p. 61.

- ^ English 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Burgess 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Bricker & Wright 2005, p. 16.

- ^ "Exploring Canadian values" (PDF). Nanos Research. October 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Blackwell 2005.

- ^ Armstrong 2010, p. 144.

- ^ "Canada in the Making: Pioneers and Immigrants". The History Channel. August 25, 2005. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ White & Findlay 1999, p. 67.

- ^ Dufour 1990, p. 25.

- ^ "Original text of The Quebec Act of 1774". Canadiana (Library and Archives Canada). 2004. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "American Civil War and Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Foundation. 2003. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ Vaillancourt & Coche 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Magocsi 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Nersessian 2007.

- ^ "Forging Our Legacy: Canadian Citizenship And Immigration, 1900–1977 – The growth of Canadian nationalism". Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2006. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ Linteau, Durocher & Robert 1983, p. 522.

- ^ "Canada and the League of Nations". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. 2007. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Bodvarsson & Van den Berg 2009, p. 380.

- ^ Prato 2009, p. 50.

- ^ Duncan & Ley 1993, p. 205.

- ^ Wayland 1997.

- ^ "Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Being Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982)". Electronic Frontier Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ "Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1985, c. 24 (4th Supp.))". Department of Justice Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on February 18, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Douglas Baer, Edward Grabb, and William Johnston, "National character, regional culture, and the values of Canadians and Americans." Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 30.1 (1993): 13-36.

- ^ a b "Exploring Canadian values" (PDF). nanosresearch.com. Values Survey Summary - Survey by Nanos Research, October 2016. July 28, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Understanding Canadians". Simon Fraser University. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ a b "2016-10-24 Exploring Canadian values – Nanos Research". Nanos Research. October 24, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- ^ "Perceptions of shared values in Canadian society among the immigrant population". Statistics Canada. January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ McKay, Ian (2005). Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada's Left History. Between The Lines. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-896357-97-3.

- ^ Doug Baer, et al. "The values of Canadians and Americans: A critical analysis and reassessment Archived May 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine". Social Forces 68.3 (1990): 693–713.

- ^ Seymour Martin Lipset (1991). Continental Divide: The Values and Institutions of the United States and Canada. Psychology Press. pp. 42–50. ISBN 978-0-415-90385-1.

- ^ MacDonald, Neil (September 13, 2016). "A very short list of Canadian values: Neil Macdonald". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Stairs, Denis (2003). "Myths, Morals, and Reality in Canadian Foreign Policy". International Journal. 58 (2): 239–256. doi:10.2307/40203840.

- ^ The Environics Institute (2010). "Focus Canada (Final Report)" (PDF). Queen's University. p. 4 (PDF page 8). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Canadian Identity, 2013". Statistics Canada. October 1, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ "Canadian Identity". The Canadian Encyclopedia. November 16, 1981. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

- ^ Gwyn, Richard J. (2008). John A: The Man Who Made Us. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-679-31476-9.

- ^ Foran, Charles (January 4, 2017). "The Canada experiment: is this the world's first 'postnational' country?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ William H. Mobley; Ming Li; Ying Wang (2012). Advances in Global Leadership. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-78052-003-2.

- ^ "The death of the Laurentian consensus and what it says about Canada". Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Freedom of Religion – by Marlene Hilton Moore". McMurtry Gardens of Justice. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ Dianne R. Hales; Lara Lauzon (2009). An Invitation to Health. Cengage Learning. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-17-650009-2.

- ^ a b Cornelissen, Louis (October 28, 2021). "Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019". Statistics Canada.

- ^ Moon, Richard (2008). Law and Religious Pluralism in Canada. UBC Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-7748-1497-3.

- ^ Scott, Jamie S. (2012). The Religions of Canadians. University of Toronto Press. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-4426-0516-9.

- ^ Lance W. Roberts (2005). Recent Social Trends in Canada, 1960–2000. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-7735-2955-7.

- ^ Paul Bramadat; David Seljak (2009). Religion and Ethnicity in Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7.

- ^ Kurt Bowen (2004). Christians in a Secular World: The Canadian Experience. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7735-7194-5.

- ^ Derek Gregory; Ron Johnston; Geraldine Pratt; Michael Watts; Sarah Whatmore (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography. John Wiley & Sons. p. 672. ISBN 978-1-4443-1056-6.

- ^ Betty Jane Punnett (2015). International Perspectives on Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-317-46745-8.

- ^ Dr. David M. Haskell (Wilfrid Laurier University) (2009). Through a Lens Darkly: How the News Media Perceive and Portray Evangelicals. Clements Publishing Group. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-894667-92-0.

- ^ Kevin Boyle; Juliet Sheen (2013). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. University of Essex – Routledge. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-134-72229-7.

- ^ Ruth M. Underhill (1965). Red Man's Religion: Beliefs and Practices of the Indians North of Mexico. Chicago, Il; London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-84167-7.

- ^ Åke Hultkrantz (1987). "North American Indian Religions: An Overview". In Mircea Eliade (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 10. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-909810-6 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Arlene Hirschfelder; Paulette Molin (2000) [1992]. Encyclopedia of Native American Religions: An Introduction. Foreword by Walter R. Echo-Hawk (Updated ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-3949-6.

- ^ Derek G. Smith (December 3, 2011). "Religion and Spirituality of Indigenous Peoples in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ McShea, B. (2022). Apostles of Empire: The Jesuits and New France. France Overseas: Studies in Em. Nebraska. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4962-2908-3. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Findling, John E.; Thackeray, Frank W. (December 9, 2010). What Happened? An Encyclopedia of Events That Changed America Forever [4 volumes]. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59884-621-8. OCLC 639162714.

- ^ Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada (January 1, 2016). Canada's Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume I. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–7. ISBN 978-0-7735-9818-8.

- ^ Choquette, R. (2004). Canada's Religions: An Historical Introduction. Religion and Beliefs Series. University of Ottawa Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7766-1847-0. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ "Orthodox Church". The Canadian Encyclopedia. December 16, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Jamie S. (2013). The Religions of Canadians. ISBN 978-1-4426-0517-6.

- ^ "Canada in the Making: Pioneers and Immigrants". The History Channel. August 25, 2005.

- ^ Cormier, Jeffrey (2004). The Canadianization Movement: Emergence, Survival, and Success. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442680616. ISBN 9781442680616.

- ^ a b Symbols of Canada. Canadian Government Publishing. 2002. ISBN 978-0-660-18615-3.

- ^ "Maple Leaf Tartan becomes official symbol". Toronto Star. March 9, 2011.

- ^ Gough, Barry M. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Canada. Scarecrow Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8108-7504-3.

- ^ Nischik, Reingard M. (2008). History of Literature in Canada: English-Canadian and French-Canadian. Camden House. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-1-57113-359-5.

- ^ Sociology in Action (2nd Canadian ed.). Nelson Education-McGraw-Hill Education. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-17-672841-0.

- ^ Hutchins, Donna; Hutchins, Nigel (2006). The Maple Leaf Forever: A Celebration of Canadian Symbols. The Boston Mills Press. p. iix. ISBN 978-1-55046-474-0.

- ^ a b Berman, Allen G (2008). Warman's Coins And Paper Money: Identification and Price Guide. Krause Publications. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4402-1915-3.

- ^ "2006 Census: The Evolving Linguistic Portrait, 2006 Census: Highlights". Statistics Canada, Dated 2006. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ a b Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (February 8, 2017). "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ Gordon 2005.

- ^ Kockaert & Steurs 2015, p. 490.

- ^ Grimes & Grimes 2000.

- ^ Schuit, Baker & Pfau 2011.

- ^ a b "Official Languages Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.))". Act current to 2016-08-29 and last amended on 2015-06-23. Department of Justice. September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Nunavut's Languages". Office of the Languages Commissioner of Nunavut. Archived from the original on September 4, 2010. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ "Highlights of the Official Languages Act". Legislative Assembly of the NWT. 2003. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Ha & Ganahl 2006, p. 62.

- ^ Winford 2003, p. 183.

- ^ Wurm, Muhlhausler & Tyron 1996, p. 1491.

- ^ Pfau, Steinbach & Woll 2012, p. 540.

Bibliography

- Agnew, Vijay (2007). Interrogating Race and Racism. Toronto UP. ISBN 978-0-8020-9509-1.

- Armstrong, Robert (2010). Broadcasting Policy in Canada. U Toronto P. ISBN 978-1-4426-1035-4.

- Blackwell, John D. (2005). "Culture High and Low". International Council for Canadian Studies World Wide Web Service. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- Bloemraad, Irene (2006). Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants And Refugees in the United States And Canada. U Cal P. ISBN 978-0-520-24898-4.

- Bloomberg, Jon (2004). The Jewish World in the Modern Age. KTAV Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88125-844-8.

- Bodvarsson, Örn Bodvar & Van den Berg, Hendrik (2009). The economics of immigration: theory and policy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-77795-3.

- Borrows, John (2010). Canada's Indigenous Constitution. Toronto UP. ISBN 978-1-4426-1038-5.

- Kockaert, Hendrik J.; Steurs, Frieda (March 13, 2015). Handbook of Terminology. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-6956-0.

- Bowen, Kurt (2005). Christians in a Secular World: The Canadian Experience. MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2712-6.

- Boyle, Kevin & Sheen, Juliet, eds. (1997). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. U Essex – Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15977-7.

- Bramadat, Paul & Seljak, David (2009). Religion and Ethnicity in Canada. U Toronto P. ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7.

- Bricker, Darrell & Wright, John (2005). What Canadians Think About Almost Everything. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-65985-7.

- Burgess, Ann Carroll (2005). Guide to Western Canada. GPP. ISBN 978-0-7627-2987-6.

- Bybee, Rodger W. & McCrae, Barry (2009). Pisa Science 2006: Implications for Science Teachers and Teaching. NSTA. ISBN 978-1-933531-31-1.

- Cameron, Elspeth, ed. (2004). Multiculturalism and Immigration in Canada: An Introductory Reader. Canadian Scholars'. ISBN 978-1-55130-249-2.

- Campey, Lucille H. (2008). Unstoppable Force: The Scottish Exodus to Canada. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55002-811-9.

- Chase, Steven; Curry, Bill & Galloway, Gloria (May 6, 2008). "Thousands of illegal immigrants missing: A-G". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Coates, Colin MacMillan, ed. (2006). Majesty in Canada: Essays on the Role of Royalty. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-586-6.

- Cornelius, Wayne A.; Tsuda, Takeyuk; Martin, Philip; Hollifield, James, eds. (2004). Controlling immigration: a global perspective. Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-4490-4.

- Coward, Harold G.; Hinnells, John Russell & Williams, Raymond Brady (2000). The South Asian religious diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9302-1.

- Coward, Harold G. & Kawamura, Leslie S. (1979). Religion and Ethnicity: Essays. Wilfrid Laurier UP. ISBN 978-0-88920-064-7.

- Day, Richard J. F. (2000). Multiculturalism and the History of Canadian Diversity. Toronto UP. ISBN 978-0-8020-8075-2.

- DeRocco, David & Chabot, John F. (2008). From Sea to Sea to Sea: A Newcomer's Guide to Canada. Full Blast Productions. ISBN 978-0-9784738-4-6.

- DeVoretz, Don J. (2011). "Canada's Secret Province: 2.8 Million Canadians Abroad" (PDF). Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- Dufour, Christian (1990). A Canadian Challenge Le Defi Quebecois. Oolichan / IRPP. ISBN 978-0-88982-105-7.

- Duncan, James S. & Ley, David, eds. (1993). Place/culture/representation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09451-1.

- Elliott, Bruce S. (2004). Irish Migrants in the Canadas: A New Approach (2nd ed.). MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2321-0.

- English, Allan D. (2004). Understanding Military Culture: A Canadian Perspective. MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2715-7.

- Feltes, Norman N. (1999). This Side of Heaven: Determining the Donnelly Murders, 1880. Toronto UP. ISBN 978-0-8020-4486-0.

- Findling, John E. & Thackeray, Frank W., eds. (2010). What Happened? An Encyclopedia of Events That Changed America Forever. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-621-8.

- Franklin, Daniel & Baun, Michael J. (1995). Political Culture and Constitutionalism: A Comparative Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-56324-416-2.

- Good, Kristin R. (2009). Municipalities and Multiculturalism: The Politics of Immigration in Toronto and Vancouver. Toronto UP. ISBN 978-1-4426-0993-8.

- Gordon, Raymond G., ed. (2005). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15 ed.). SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6.

- Gray, Douglas (2010). The Canadian Snowbird Guide: Everything You Need to Know about Living Part-Time in the USA and Mexico. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-73942-6.

- Gregory, Derek; Johnston, Ron; Pratt, Geraldine; Watts, Michael & Whatmore, Sarah, eds. (2009). The Dictionary of Human Geography (5th ed.). Wiley–Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3288-6.

- Griffiths, N. E. S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604–1755. MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Grimes, Barbara F. & Grimes, Joseph Evans, eds. (2000). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (14 ed.). SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-103-9.

- Ha, Louisa S. & Ganahl, Richard J. (2006). Webcasting Worldwide: Business Models of an Emerging Global Medium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8058-5915-7.

- Hales, Dianne R. & Lauzon, Lara (2009). An Invitation to Health. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-17-650009-2.

- Hall, Patricia Wong & Hwang, Victor M., eds. (2001). Anti-Asian Violence in North America: Asian American and Asian Canadian Reflections on Hate, Healing, and Resistance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-0459-2.

- Harland-Jacobs, Jessica L. (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism, 1717–1927. NCUP. ISBN 978-0-8078-3088-8.

- Haskell, David M. (2009). Through a Lens Darkly: How the News Media Perceive and Portray Evangelicals. Clements Academic. ISBN 978-1-894667-92-0.

- Hobbs, Sandy; MacKechnie, Jim & Lavalette, Michael (1999). Child Labour: A World History Companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-87436-956-4.

- Hollifield, James; Martin, Philip & Orrenius, Pia, eds. (2014). Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective (third ed.). Stanford UP. ISBN 978-0-8047-8627-0.

- Huang, Annian (2006). The Silent Spikes - Chinese Laborers and the Construction of North American Railroads. Translated by Juguo Zhang. China Intercontinental Press | 中信出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0988-4.

- Hudson, John C. (2002). Across This Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHUP. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1.

- Kalman, Bobbie (2009). Canada: The culture. Crabtree. ISBN 978-0-7787-9284-0.

- Ksenych, Edward & Liu, David, eds. (2001). Conflict, Order, and Action : Readings in Sociology. Canadian Scholars'. ISBN 978-1-55130-192-1.

- Kusch, Frank (2001). All American Boys: Draft Dodgers in Canada from the Vietnam War. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-275-97268-4.

- Linteau, Paul-André; Durocher, René & Robert, Jean-Claude (1983). Quebec: A History 1867–1929. Translated by Robert Chodos. Lorimer. ISBN 978-0-88862-604-2.

- MacLeod, Roderick & Poutanen, Mary Anne (2004). Meeting of the People: School Boards and Protestant Communities in Quebec, 1801–1998. MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2742-3.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1999). Multicultural History Society of Ontario (ed.). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. U Toronto P. ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2002). Aboriginal Peoples of Canada: A Short Introduction. U Toronto P. ISBN 978-0-8020-8469-9.

- Martens, Klaus, ed. (2004). The Canadian Alternative (in German). Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-2636-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Martynowych, Orest T (1991). Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891–1924. CIUS Press, U Alberta. ISBN 978-0-920862-76-6.

- McGowan, Mark G., ed. (1999). "Irish Catholics: Migration, Arrival, and Settlement before the Great Famine". The Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. Multicultural Canada. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012.

- McGowan, Mark (2009). Death or Canada: the Irish Famine Migration to Toronto 1847. Novalis. ISBN 978-2-89646-129-5.

- Melton, J. Gordon & Baumann, Martin, eds. (2010). Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-203-6.

- Miedema, Gary (2005). For Canada's Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, and the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s. MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-2877-2.

- Murrin, John M.; Johnson, Paul E.; McPherson, James M.; Fahs, Alice; Gerstle, Gary; Rosenberg, Emily S. & Rosenberg, Norman L. (2007). Liberty, Equality, Power, A History of the American People: To 1877 (5th ed.). (Wadsworth) Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-11606-6.

- Naik, C. D. (2003). Thoughts and Philosophy of Doctor B. R. Ambedkar. Sarup. ISBN 978-81-7625-418-2.

- Nersessian, Mary (April 9, 2007). "Vimy battle marks birth of Canadian nationalism". CTV Television Network. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- Pfau, Roland; Steinbach, Markus & Woll, Bencie, eds. (2012). Sign Language: An International Handbook. de Gruyter / Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-026132-5.

- Powell, John (2005). Encyclopedia of North American immigration. InfoBase. ISBN 978-0-8160-4658-4.

- Prato, Giuliana B., ed. (2009). Beyond multiculturalism: Views from Anthropology. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-7173-2.

- Schneider, Stephen (2009). Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-83500-5.

- Schuit, Joke; Baker, Anne & Pfau, Roland (2011). "Inuit Sign Language: a contribution to sign language typology" (pdf). Amsterdam Center for Language and Communication Working Papers (ACLC). 4 (1). U Amsterdam: 1–31.

- Standford, Frances (2000). Development of Western Canada Gr. 7–8. On The Mark Press. ISBN 978-1-77072-743-4.

- Tooker, Elisabeth (1980). Native North American spirituality of the eastern woodlands: sacred myths, dreams, visions, speeches, healing formulas, rituals, and ceremonials. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-2256-1.

- Vaillancourt, François & Coche, Olivier (2009), "Official Language Policies at the Federal Level in Canada: Costs and Benefits in 2006" (PDF), Studies in Language Policy, Fraser Institute, ISSN 1920-0749

- Waugh, Earle Howard; Abu-Laban, Sharon McIrvin & Qureshi, Regula (1991). Muslim families in North America. U Alberta. ISBN 978-0-88864-225-7.

- Wayland, Shara V. (1997). "Immigration, Multiculturalism and National Identity in Canada". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 5 (1). Dept of Political Science, U Toronto: 33–58. doi:10.1163/15718119720907408.

- White, Richard & Findlay, John M., eds. (1999). Power and Place in the North American West. UWP. ISBN 978-0-295-97773-7.

- Wilkinson, Paul F. (1980). In celebration of play: an integrated approach to play and child development. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-41078-0.

- Winford, Donald (2003). An Introduction to Contact Linguistics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-21250-8.

- Wurm, Stephen Adolphe; Muhlhausler, Peter & Tyron, Darrell T., eds. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. de Gruyter / Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Yamagishi, N. Rochelle (2010). Japanese Canadian Journey: The Nakagama Story. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4269-8148-7.

- Zimmerman, Karla (2008). Canada (tenth ed.). Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-571-0.

Further reading

- Beaty, Bart; Briton, Derek; Filax, Gloria (2010). How Canadians Communicate III: Contexts of Canadian Popular Culture. Athabasca University Press. ISBN 978-1-897425-59-6.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2003). Canada's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-672-9.

- Carment, David; Bercuson, David (2008). The World in Canada: Diaspora, Demography, and Domestic Politics. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-7455-7.

- Cohen, Andrew (2008). The Unfinished Canadian: The People We Are. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-2286-9.

- Gillmor, Don; Turgeon, Pierre (2002). CBC (ed.). Canada: A People's History. Vol. 1. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3324-7.

- Gillmor, Don; Turgeon, Pierre; Michaud, Achille (2002). CBC (ed.). Canada: A People's History. Vol. 2. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3336-0.

- Kearney, Mark; Ray, Randy (2009). The Big Book of Canadian Trivia. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-77070-614-9.

- Kelley, Ninette; Trebilcock, M. J. (2010). The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- Resnick, Philip (2005). The European Roots of Canadian Identity. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-705-8.

- Richard, Madeline A. (1992). Ethnic Groups and Marital Choices: Ethnic History and Marital Assimilation in Canada, 1871 and 1971. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0431-8.

- Simpson, Jeffrey (2000). Star-Spangled Canadians: Canadians Living the American Dream. Harper-Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-255767-2.

- Studin, Irvin (2006). What Is a Canadian?: Forty-Three Thought-Provoking Responses. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-8321-1.

External links

- Canada Year Book 2010 – Statistics Canada

- Canada: A People's History – Teacher Resources – Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Persons of National Historic Significance in Canada[permanent dead link] – Parks Canada

- Multicultural Canada – Department of Canadian Heritage

- The Canadian Immigrant Experience – Library and Archives Canada

- The Dictionary of Canadian Biography – Library and Archives Canada

- Canadiana: The National Bibliography of Canada – Library and Archives Canada