2003 Ontario general election

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

103 seats in the 38th Legislative Assembly of Ontario 52 seats were needed in a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 56.87% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

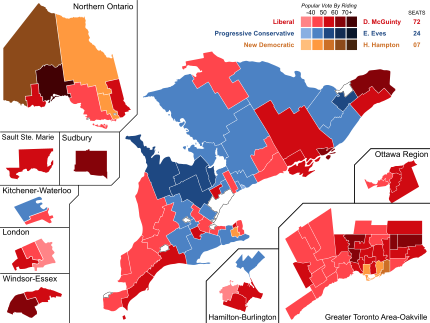

Popular vote by riding. As this is an FPTP election, seat totals are not determined by popular vote, but instead via results by each riding. Click the map for more details. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2003 Ontario general election was held on October 2, 2003, to elect the 103 members of the 38th Legislative Assembly (Members of Provincial Parliament, or "MPPs") of the province of Ontario, Canada.

The election was called on September 2 by Premier Ernie Eves in the wake of supporting polls[1] for the governing Ontario Progressive Conservative Party in the days following the 2003 North American blackout. The election resulted in a majority government won by the Ontario Liberal Party, led by Dalton McGuinty.

Leadup to the campaign

[edit]In 1995, the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party under Mike Harris came from third place to upset the front-running Ontario Liberal Party under Lyn McLeod and the governing Ontario New Democratic Party under Bob Rae to form a majority government. Over the following two terms, the Harris government moved to cut personal income tax rates by 30%, closed almost 40 hospitals to increase efficiency, cut the Ministry of the Environment staff in half, and undertook massive reforms of the education system, including mandatory teacher testing, student testing in public education, and public tax credits for parents who sent their children to private schools.

In the 1999 provincial election, the Tories were able to ride a strong economy and a campaign aimed at depicting rookie Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty as "not up to the job" to another majority government. The Walkerton Tragedy, however, where a contaminated water supply led to the deaths of 7 people and illness of at least 2,300 were linked in part to government environment and regulatory cutbacks, and as a result the government's popularity was badly damaged. A movement to provide tax credits to parents with children in private schools also proved to be unpopular.

In October 2001, Harris announced his intention to resign,[2] and the PC party called a leadership convention for 2002 to replace him. Five candidates emerged: former Finance Minister Ernie Eves who had retired earlier that year, current Finance Minister Jim Flaherty, Environment Minister Elizabeth Witmer, Health Minister Tony Clement and Labour Minister Chris Stockwell.[2] The resulting leadership election was divisive in the PC Party, with Flaherty adopting a hard-right platform and attacking the front-running Eves as "a pale, pink imitation of Dalton McGuinty" and a "serial waffler". At one point, anti-abortion activists apparently supporting Flaherty distributed pamphlets attacking Tony Clement because his wife worked for hospitals that performed abortions. At the convention, Eves won on the second ballot after Elizabeth Witmer and Tony Clement both endorsed him.

Eves took office on April 15, 2002, and promptly re-aligned his government to the political centre. The party would negotiate a deal with striking government workers, dramatically cancel an IPO of Hydro One, the government's electricity transmission company, and defer planned tax breaks for corporations and private schools for a year. With polls showing the Conservatives moving from a 15-point deficit to a tie in public opinion with the Liberals, the media praising Eves' political reorientation of the government, and the opposition Liberals reeling from the seizure of some of their political turf, the time seemed ripe for a snap election call. Many political observers felt that Eves had the momentum to win an election at that time.

However, several factors likely convinced Eves to wait to call an election. First, in 1990, the Liberals had lost the election in part due to perceptions that they called the election early for purely partisan reasons. Since then, the shortest distance between elections had been four years less five days (Ontario has since moved to fixed date election dates). Second, the PC Party was exhausted and divided from a six-month leadership contest. Third, the move to the centre had created opposition in traditional Conservative support. Financial conservatives and businesses were angered over Eves' cancellation of the hydro IPO. Others felt betrayed that promised tax cuts had not been delivered, seemingly breaking the PCs' own Taxpayer Protection Act, while private school supporters were upset their promised tax credit had been delayed for a year.

In the fall of 2002, the opposition Liberals began a round of attacks on perceived PC mismanagement. First, Jim Flaherty was embroiled in scandal when it was revealed that his leadership campaign's largest donor had received a highly lucrative contract for slot machines from the government.[3] Then, Tourism Minister Cam Jackson was forced to resign when the Liberals revealed he had charged taxpayers more than $100,000 for hotel rooms, steak dinners and alcoholic beverages.[4] The Liberals showed the Tories had secretly given a large tax break to the Toronto Blue Jays, a team owned by prominent Tory Ted Rogers.

At the same time, both the New Democrats and Liberals criticized the government over skyrocketing electricity prices. In May 2002, the government had followed California and Alberta in deregulating the electricity market. With contracting supply due to construction delays at the Pickering nuclear power plant and rising demand for electricity in an unusually warm autumn, the spot price for electricity rose, resulting in consumer outrage. In November, Eves fixed the price of electricity and ended the open market, appeasing consumers but angering conservative free-marketers.

That winter, Eves promised a provincial budget before the beginning of the fiscal year, to help hospitals and schools budget effectively. However, as multiple scandals in the fall had already made the party unwilling to return to Question Period, they wished to dismiss the Legislative Assembly of Ontario until as late as possible in the spring. The budget was instead to be announced at the Magna International headquarters in Newmarket, Ontario, rather than in the Legislature. The move was met with outrage from the PC Speaker Gary Carr, who called the move unconstitutional and would rule that it was a prima facie case of contempt of the legislature. The controversy over the location of the budget far outstripped any support earned by the content of the budget.

The government faced a major crisis when SARS killed several people in Toronto and threatened the stability of the health care system. On April 23, when the World Health Organization advised against all but essential travel to Toronto to prevent the spread of the virus, Toronto tourism greatly suffered.

When the spring session was finally convened in late spring, the Eves government was forced through three days of debate on the contempt motion over the Magna budget followed by weeks of calls for the resignation of Energy Minister Chris Stockwell. Stockwell was accused of accepting thousands of dollars in undeclared gifts from Ontario Power Generation, an arms-length crown corporation he regulated, when he travelled to Europe in the summer of 2002. Stockwell finally stepped aside after dominating the provincial news for almost a month, and did not seek reelection.

By the summer of 2003, the Progressive Conservatives received an unexpected opportunity to re-gain popularity in the form of the 2003 North American blackout. When the blackout hit, Eves initially received criticism for his late response; however, as he led a series of daily briefings to the press in the days after the blackout, Eves was able to demonstrate leadership and stayed cool under pressure. The crisis also allowed Eves to highlight his principal campaign themes of experience, proven competence and ability to handle the government. When polls began to register a moderate increase for the Conservatives, the table was set for an election call.

Progressive Conservative campaign

[edit]In 1995 and 1999, the Progressive Conservatives ran highly focused, disciplined campaigns based on lessons learned principally in US states by the Republican Party. In 1995, the core PC strategy was to polarize the electorate around a handful of controversial ideas that would split opposition between the other two parties. The PCs stressed radical tax cuts, opposition to job quotas, slashing welfare rates and a few hot button issues such as opposing photo radar and establishing "boot camps" for young offenders. They positioned leader Mike Harris as an average-guy populist who would restore common sense to government after ten lost years of NDP and Liberal mismanagement. The campaign manifesto, released in 1994, was titled the "Common Sense Revolution" and advocated a supply-side economics solution to a perceived economic malaise.

In 1999, the PCs were able to point to increased economic activity as evidence that their supply side plan worked. Their basic strategy was to polarize the electorate again around a handful of controversial ideas and their record while preventing opposition from rallying exclusively around the Liberals by undermining confidence in Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty. They ran a series of negative television ads against McGuinty in an attempt to brand him as "not up to the job". At the same time, they emphasized their economic record, while downplaying disruptions in health care and education as part of a needed reorganization of public services that promoted efficiency and would lead to eventual improvements.

Both campaigns proved highly successful and the principal architects of those campaigns had been dubbed the "whiz kids" by the press. David Lindsay, Mike Harris's chief of staff, was responsible for the overall integration of policy, communications, campaign planning and transition to government while Mitch Patten served as campaign secretary. Tom Long and Leslie Noble jointly ran the campaigns, with Long serving as campaign chair and Noble as campaign manager. Paul Rhodes, a former reporter, was responsible for media relations. Deb Hutton was Mike Harris's right arm as executive assistant. Jaime Watt and Perry Miele worked on the advertising. Guy Giorno worked on policy and speechwriting in 1995 and in 1999 was in charge of overall messaging. Scott Munnoch was tour director and Glen Wright rode the leader's bus. Future leader John Tory worked on fundraising and debate prep, and was actually one of two people (the other was John Matheson) to play Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty during preparation for the 1999 leaders' debate. (Andy Brandt and Giorno played NDP leader Howard Hampton.)

Heading into 2003, Tom Long refused to work for Ernie Eves. Most speculated that Long saw Eves as too wishy-washy and not enough of a traditional hard-right conservative. Jaime Watt took Long's position as campaign co-chair and more or less all the same players settled into the same places. A few new faces included Jeff Bangs as campaign manager. Bangs was a long-time Eves loyalist who had grown up in his riding of Parry Sound.

The Progressive Conservatives once again planned on polarizing the electorate around a handful of hot button campaign pledges. However, with their party and government listing in public opinion polls, they found their only strong contrasts were around the experience and stature of Premier Eves. Their campaign slogan "Experience You Can Trust" was designed to highlight Eves' years in office.

The party platform, dubbed "The Road Ahead", was longer and broader than in earlier years. Five main planks would emerge for the campaign:

- Tax deductions for mortgage payments.

- Rebate seniors the education portion of their property taxes.

- Tax credits for parents sending their children to private schools.

- Banning teachers' strikes by sending negotiations to binding arbitration.

- A "Made-in-Ontario" immigration system.

Each plank was targeted at a key Tory voting bloc: homeowners, seniors, religious conservatives, parents and law-and-order types.

Eves' campaigning followed a straightforward pattern. Eves would highlight one of the five elements of the platform and then attack Dalton McGuinty for opposing it. For instance, he would visit the middle-class home of a visible minority couple with two kids and talk about how much money they would get under his mortgage deductibility plan. That would be followed by an attack on McGuinty for having a secret plan to raise their taxes. Or he would campaign in a small town assembly plant and talk about how under a "Made-in-Ontario" immigration plan fewer new Canadians would settle in Toronto and more outside the city, helping the plant manager with his labour shortage. Then he would link McGuinty to Prime Minister of Canada Jean Chrétien and say McGuinty supported the federal immigration system that allows terrorists and criminals into the country.

The Tory television advertising also attempted to polarize the election around these issues.

In one of the ads, a voice-over accompanying an unflattering photo of the Liberal leader asks "Ever wonder why Dalton McGuinty wants to raise your taxes?" The ad then points out that McGuinty has opposed Tory plans to allow homeowners a tax deduction on mortgage interest and to give senior citizens a break on their property taxes.

In another ad, the voice-over asks "Doesn't he (McGuinty) know that a child's education is too important to be disrupted by lockouts and strikes?" It says that McGuinty has sided with the unions and rejected the Tory proposal to ban teacher strikes.

Both ads end with the attack "He's still not up to the job."

Armed with a majority, the Tories were hoping to hold the seats they already had, while targeting a handful of rural Liberal seats in hopes of increasing their majority. They campaigned relatively little in Northern Ontario, with the exception of North Bay and Parry Sound, both of which they held.

Liberal campaign

[edit]The first half of Dalton McGuinty's 1999 campaign was widely criticized as disorganized and uninspired, and most journalists believe he gave a poor performance in the leaders' debate. McGuinty, however, was able to rally his party in the last ten days. On election day, the Liberals won 40% of the vote, their second best showing in almost fifty years. Perhaps more importantly, nine new MPPs were elected, boosting the caucus from 30 to 35, including dynamic politicians like George Smitherman and Michael Bryant.

In 1999, the Liberal strategy had been to polarize the electorate between Mike Harris and Dalton McGuinty. They purposely put out a platform that was devoid of ideas, to ensure the election was about the Tory record, and not the Liberal agenda. To an extent, they succeeded. Support for the NDP collapsed from 21% to just 13%, while the Liberals climbed by 9%. While they almost cornered the market of those angry at the Tories, however, they could not convince enough people to be angry at the Tories to win.

The night he conceded defeat, McGuinty was already planning how to win the next election. He set out the themes that the Liberals would build into their next platform. Liberals, he said, would offer "some of those things that Ontarians simply have to be able to count on - good schools, good hospitals, good health care, good education and something else.... We want to bring an end to fighting so we can finally start working together."

McGuinty replaced many of his young staff with experienced political professionals he recruited. The three he kept in key positions were Don Guy, his campaign manager and a pollster with Pollara, Matt Maychak, his director of communications, and Bob Lopinski, his director of issues management. To develop his platform, he added to this a new chief of staff, Phil Dewan, a former policy director for Premier David Peterson and Ottawa veteran Gerald M. Butts. He also sought out Peterson-era Ontario Minister of Labour Greg Sorbara to run for president of the Ontario Liberal Party.

Early on, McGuinty set down three strategic imperatives. First, no tax cuts. This ran against the conventional wisdom of politics that it was necessary to offer tax cuts to win; everyone from Mike Harris to Bill Clinton had campaigned on reducing the tax burden on the middle class. But McGuinty was determined that Ontario voters would accept that the money was needed to restore public health care and education services. Second, a positive tone. McGuinty wanted to avoid the typical opposition leader role of automatically opposing whatever the government announced, and instead, set the agenda with positive alternatives. While attacking the opponent was important, that would be left to caucus surrogates. Third, one big team. At the time, the Ontario Liberal Party was riven into factions. Peterson-era people distrusted more recent arrivals. Jean Chrétien supporters fought with Paul Martin supporters. McGuinty set a tone that divisions were left at the door.

The emphasis on building the team was highly successful as jobs that in 1999 were done by one person were now assigned to groups of four or six or eight. Dewan brought on board veterans of the Peterson regime such as Sheila James, Vince Borg and David MacNaughton. From Ottawa, campaign veterans such as Warren Kinsella, Derek Kent and Gordon Ashworth signed on to help oust the Ontario Tories from power.

The Liberal strategy was the same as in 1999: polarize the election between the Conservatives and Liberals to marginalize the NDP and then convince enough voters that the Conservatives had to go. With polls showing more than 60% of voters reporting it was "time for a change", the Liberals campaign theme was "choose change". The theme summarized the two-step strategy perfectly: first, boil the election down to a two-party choice and then cast the Liberals as a capable and trustworthy agent of change at a time when voters were fed up with the government.

After the sparse platform of 1999, the 2003 Liberal platform was a sprawling omnibus of public policy crossing five main policy booklets, three supplements aimed at specific geographic or industrial groups and a detailed costing exercise. The principle planks that were highlighted in the election were:

- Freezing taxes and balancing the books.

- Improving test scores and lowering class sizes in public schools.

- Reducing wait times for key health services.

- Improving environmental protection and quality of life.

- Repairing the divisions of the Harris-Eves era.

McGuinty backed up his comprehensive platform with a meticulous costing by a forensic accountant and two bank economists. While the Conservatives had adopted a third-party verification in 1995, they did not in 2003, allowing the Liberals to gain credibility that they could pay for their promises.

In contrast to the Eves campaign, where the leader was both positive and negative message carrier, the Liberals used a number of caucus members to criticize the Harris-Eves government while McGuinty was free to promote his positive plan for change.

The Liberal advertising strategy was highly risky. While conventional wisdom says the only way to successfully respond to a negative campaign is with even more negative ads against the opponent, McGuinty ran only positive ads for the duration of the campaign.

In the pre-writ period, the Liberal advertising featured Dalton McGuinty speaking to the camera, leaning against a tree while snow falls, saying "People hear me say that I'll fix our hospitals and fix our schools and yet keep taxes down. Am I an optimist? Maybe. What I'm not is cynical, or jaded, or tired. I don't owe favours to special interests or old friends or political cronies. Together, we can make Ontario the envy of the world, once again. And, I promise you this, no one will work harder than I will to create that Ontario."

During the first stage of the campaign, the principal Liberal ad featured a tight close-up of Dalton McGuinty as he spoke about his plans for Ontario. In the key line of the first ad, McGuinty looks into the camera and says "I won't cut your taxes, but I'm not going to raise them either."

Geographically, the Liberal campaign was able to rest on a solid core of seats in Toronto and Northern Ontario that were at little risk at the beginning of the election period. They had to defend a handful of rural seats that had been recently won and were targeted by the PCs. The principle battlefield of the election, however, was in PC-held territory in the "905" region of suburbs around Toronto, particularly Peel and York districts, suburban seats around larger cities like Ottawa and Hamilton and in Southwestern Ontario in communities like London, Kitchener-Waterloo and Guelph.

NDP campaign

[edit]The 1999 NDP campaign received its lowest level of popular support since the Second World War, earning just 12.6% of the vote and losing party status with just nine seats. Several factors led to this poor showing, including a lacklustre campaign, Hampton's low profile, and a movement called strategic voting that endorsed voting for the Liberals in most ridings in order to remove the governing Tories. After the election, there was a short-lived attempt to remove leader Howard Hampton publicly led by leaders of the party's youth wing, however the majority of party members blamed the defeat on NDP supporters voting Liberal in hopes of removing Harris and the Tories from power. As a result, Hampton was not widely blamed for this severe defeat and stayed on as leader.

Under the rules of the Legislative Assembly, a party would receive "official party status", and the resources and privileges accorded to officially recognized parties, if it had 12 or more seats; thus the NDP would lose caucus funding and the ability to ask questions in the House, however the governing Conservatives changed the rules after the election to lower the threshold for party status from 12 seats to 8. The Tories argued that since Ontario's provincial ridings now had the same boundaries as the federal ones, the threshold should be lowered to accommodate the resultant smaller legislature. Others argued that the Tories were only helping the NDP so they could continue to split the vote with the Liberals.

During the period before the election, Hampton identified the Conservative plan for deregulating and privatizing electricity generation and transmission as the looming issue of the next election. With the Conservatives holding a firm market-oriented line and the Liberal position muddled, Hampton boldly focused the party's Question Period and research agendas almost exclusively on energy issues. Hampton quickly distinguished himself as a passionate advocate of maintaining public ownership of electricity generation, and published a book on the subject, Public Power, in 2003.

With the selection of Eves as the PC leader, the NDP hoped that the government's move to the centre in the spring of 2002 would reduce the polarization of the Ontario electorate between the PCs and Liberals and improve the NDP's standing. It was also hoped that the long-standing split between labour and the NDP would be healed as the bitter legacy of the Rae government faded.

The co-chairs of the NDP campaign were Diane O'Reggio, newly installed as the party's provincial secretary after a stint in Ottawa working for the federal party, and Andre Foucault, secretary-treasurer of the Communications Energy and Paperworkers union. The manager was Rob Milling, principal secretary to Hampton. Communications were handled by Sheila White and Gil Hardy. Jeff Ferrier was the media coordinator.

The NDP strategy was to present itself as distinct from the Liberals on the issue of public ownership of public services, primarily in electricity and health care, while downplaying any significant differences between the Liberals and PCs. There was a conscious effort to discourage "strategic voting" where NDP supporters vote Liberal to defeat the Conservatives. The NDP slogan was "publicpower", designed to highlight both the energy issue Hampton had championed and public health care, while promoting a populist image of empowerment for average people.

The NDP campaign was designed to be highly visual and memorable. Each event was built around a specific visual thematic. For instance, in the first week of the campaign, Hampton attacked the Liberal energy platform saying it was "full of holes" and holding up a copy of the platform with oversized holes punched in it. He also illustrated it "had more holes than Swiss cheese" by also displaying a large block of cheese. At another event, Hampton and his campaign team argued that the Liberal positions were like "trying to nail Jello to the wall" by literally attempting to nail Jello to a wall. Hampton also made an appearance in front of the Toronto home of millionaire Peter Munk to denounce Eves' tax breaks, claiming that they would save Munk $18,000 a year.

The first round of NDP ads avoided personal attacks, and cast leader Howard Hampton as a champion of public utilities. In one 30-second spot, Mr. Hampton talks about the effects of privatization of the power industry and the blackout. "For most of us, selling off our hydro was the last straw," he says. The clip is mixed with images of Toronto streets during power failure.

Geographically, the NDP campaign focused on targeting seats in Scarborough and Etobicoke in Toronto, Hamilton, Ottawa and Northern Ontario.

Campaign events

[edit]Early weeks

[edit]The first week of the campaign was dominated by the Conservatives, who launched a series of highly negative attacks at Liberal leader Dalton McGuinty while highlighting popular elements of their platform. On the first week of the campaign, two polls showed a tight race: a poll done by EKOS for the Toronto Star showed a 1.5% Liberal lead, while a smaller poll done by COMPAS showed a 5% Liberal lead.[5] A poll done by Environics in late June and early July showed a 13-point lead for the Liberals.[6]

As the campaign entered week 2, it was anticipated that the Liberals would push a series of highly negative ads to combat advertising by the Conservatives that attacked Dalton McGuinty. Instead, they went positive and stayed positive throughout the campaign. It was Eves who went on the defensive as the Liberals worked the media to put the Premier on his heels. Stung by years of arrogance by the PC Party toward reporters, the media were quick to pile on.

After the Liberals Gerry Phillips and Gerald M. Butts accused Eves of having no plan to pay for his $10.4 billion in promises, Eves stumbled when he could not provide his own cost for his promises. "I couldn't tell you off the top of my head", he admitted.[7] Then came a story on the front of the Globe and Mail saying that Ontarians would have to pay "millions" in extra premiums because the election call had delayed implementation of new auto insurance regulations promised by Eves on the eve of the campaign.[8] On Wednesday the government was broadsided when – days after a raid at a meat packing plant exposed the sorry state of public health at some abattoirs – leaked documents showed the PC government had been sitting on recommendations to improve meat safety, leading to calls for a public inquiry by the opposition parties.[9] The issue was made worse when Agriculture Minister Helen Johns refused all media calls and had to be literally tracked down in her riding by reporters.

On Thursday, according to the Green party candidate in Nipissing (Mike Harris' old riding), a donor with Tory connections offered him money to bolster his campaign and draw votes away from the Liberals. The allegations were denied by the Tories.[10] The same day, Eves attacked Dalton McGuinty for voting against a bill to protect taxpayers from increased taxes, when it turns out McGuinty in fact voted for that bill.[11]

The "Kitten-eater" controversy

[edit]On September 12, the Eves campaign issued a news release that called Dalton McGuinty an "evil reptilian kitten-eater from another planet".[12] The words appeared at the end of the news release. Eves said the epithet was meant as a joke, and acknowledged the words were "over the top", but refused to apologize.[12]

There is speculation the epithet was an obscure reference to an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which McGuinty stated, in a blog post that week, he enjoys watching.[13]

In response, McGuinty said his campaign will not be "sidetracked" by the incident.[12] Despite efforts by two Conservative spies at a Liberal campaign event to shoo away a white kitten,[14] members of the media managed to take photographs of McGuinty holding the kitten, a moment some described as a defining moment of the campaign.[15]

Liberal Party officials made T-shirts that were emblazoned with the words "Call Me An Evil Reptilian Kitten Eater ... But I Want Change".[13] The T-shirts were handed out to party supporters at a rally held that same night.[13]

Later weeks

[edit]The Conservatives spent the third week on the defensive and dropping in the polls, unable to recover from the disasters of the second week and fresh new attacks. The Liberals produced documents from the Walkerton Inquiry showing that individual Conservative MPPs were warned about risks to human health and safety resulting from cuts to the Environment Ministry budget. An attack on Dalton McGuinty saying he needed "professional help" forced an apology from the Conservatives to people with mental illness. Tory MPP John O'Toole said the Tory negative campaign was a mistake, putting Eves on the defensive once again. A leaked memo was used by the opposition to accuse the government of threatening public sector workers into not telling the truth at a public inquiry into the government's handling of the SARS crisis. Eves ended the week with another event that backfired, brandishing barbed wire and a get out of jail free card to attack the Liberals as soft on crime. Reporters spent more time focused on Eves' first use of props in the election than on his message.

By the fourth week of the campaign, polls showed the Liberals pulling away from the Conservatives with a margin of at least 10 points. It was widely believed that only a disastrous performance in the leader's debate stood between Dalton McGuinty and the Premier's Office. McGuinty - who had stumbled badly in the 1999 debate - was able to play off low expectations and a surprisingly low-key Eves to earn the draw he wanted. The debate itself was also subject to criticism from the Green Party of Ontario, which denounced a Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission decision not to allow leader Frank de Jong to participate.[citation needed]

The final week of the campaign was marred by more negative attacks from Eves and the Conservatives. At one point, Premier Eves referred to Mr. McGuinty as having a "pointy head", a remark he later conceded was inappropriate.[16] McGuinty was able to extend the bad press from the incident another day when he joked to radio hosts that they needed to be careful "so I won't spear you with my sharp pointy head."[16]

McGuinty spent the last days of the campaign travelling through previously rock solid PC territory in ridings like Durham, Simcoe and Leeds-Grenville to large crowds.[17]

Issues

[edit]The campaign was contentious on the issues as well, with both the Liberals and Howard Hampton's New Democrats attacking the Tories' record in office. Various scandals and other unpopular moves reduced public opinion of the Tories going into the race, including the Walkerton water tragedy, the deaths of Dudley George and Kimberly Rogers, the possible sale of publicly owned electric utility Hydro One, the SARS outbreak, the decision to release the 2003 budget at an auto parts factory instead of the Legislature, the widespread blackout in August, and the Aylmer packing plant tainted meat investigation. As one Tory insider put it: "So many chickens came to roost, it's like a remake of The Birds".[18]

One of the most contentious issues was education. All three parties pledged to increase spending by $2 billion, but Premier Eves also pledged to ban teacher strikes, lock-outs, and work-to-rule campaigns during the school year, a move the other parties rejected. Teacher strikes had plagued the previous Progressive Conservative mandate of Mike Harris, whose government had deeply cut education spending.

Tax cuts were also an issue. The Progressive Conservatives proposed a wide range of tax cuts, including a 20-percent cut to personal income taxes, and the elimination of education tax paid by seniors, two moves that would have cost $1.3 billion together. The Liberals and New Democrats rejected these cuts as profligate. The Liberals also promised to cancel some pending Tory tax cuts and to eliminate some tax cuts already introduced.

Assessment

[edit]CBC Newsworld declared a Liberal victory minutes after ballot-counting began. Ernie Eves conceded defeat only ninety minutes into the count.

The Liberals won a huge majority with 72 seats, almost 70% of the 106-seat legislature. The Liberals not only won almost every seat in the city of Toronto, but every seat bordering on Toronto as well. All seven seats in Peel region went Liberal, as well as previously safe PC 905 seats such as Markham, Oakville and Pickering—Ajax. The Liberals also made a major breakthrough in Southwestern Ontario, grabbing all three seats in London as well as rural seats such as Perth–Middlesex, Huron–Bruce and Lambton–Kent. If the story of the PC majorities in 1995 and 1999 were the marriage of rural and small-town conservative bedrock with voters in the suburbs, the 2003 election was a divorce of those suburban voters from rural Ontario and a new marriage to the mid-town professionals and New Canadians who make up the Liberal base.

The NDP had a disappointingly confusing election: on one hand, they won seven seats, one fewer than the eight required to keep "official party status", which would give it a share of official Queen's Park staff, money for research, and guaranteed time during Question Period. On the other hand, they increased their share of the popular vote for the first time since 1990. Despite the mixed results, Hampton stayed on as party leader, saying that the party did not blame him for the poor performance. The party was returned to official party status seven months into the session, when Andrea Horwath won a by-election in Hamilton East on May 13, 2004.

The Tories were completely shut out of Toronto, where 19 out of 22 ridings were won by the Liberals, and the remaining three were carried by the New Democrats. Perhaps more ominously for the PCs, they were also shut out of any seats bordering Toronto; only in the outermost suburbs like Aurora and Whitby were high-profile PC cabinet ministers able to retain their seats. With the arguable exception of Elizabeth Witmer, no PC member represented an urban riding.

The 38th Parliament of Ontario opened on November 19, 2003, at 3 p.m. Eastern Time with a Throne Speech in which the McGuinty government laid out their agenda.

Student vote

[edit]High school students in every riding in Ontario were allowed to cast ballots in their classrooms as part of a student vote, although their numbers did not count in the official election. 93 ridings favoured the Liberals in the student vote, nine favoured the New Democrats, and one favoured the Greens, while the Conservatives were shut out.[19] There was also a vote for elementary students.

Opinion polls

[edit]| Polling firm | Last day of survey |

Source | OLP | PCO | ONDP | GPO | Other | ME | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election 2003 | October 2, 2003 | 46.4 | 34.6 | 14.7 | 2.8 | 1.5 | |||

| Ipsos-Reid | September 25, 2003 | [20] | 50 | 31 | 15 | — | — | — | 1,001 |

| EKOS | August 2003 | [21] | 43.5 | 42 | 13 | — | — | — | — |

| Compas | August 2003 | [22] | 46 | 41 | 12 | — | — | 4.5 | — |

| Ipsos-Reid | April 19, 2003 | [23] | 48 | 31 | 16 | 4 | — | 3.1 | 1,000 |

| Ernie Eves becomes Premier of Ontario (April 15, 2002) | |||||||||

| EKOS | March, 2003 | [24] | 49 | 36 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ipsos-Reid | February 20, 2003 | [25] | 43 | 36 | 15 | 5 | — | 3.1 | 1,000 |

| Ipsos-Reid | January 4, 2003 | [26] | 45 | 38 | 14 | 3[25] | — | 3.1 | 1,001 |

| Angus Reid | August 29, 2000 | [27] | 46 | 39 | 15 | — | 2 | 3.1 | 1,002 |

| Angus Reid | June 13, 2000 | [28] | 45 | 38 | 15 | — | 2 | 3.1 | 1,000 |

| Angus Reid | December 29, 1999 | [29] | 42 | 36 | 17 | — | 5 | 3.1 | 1,001 |

| Angus Reid | August 15, 1999 | [30] | 40 | 43 | 13 | — | 4 | 3.1 | 1,001 |

| Election 1999 | June 3, 1999 | 39.9 | 45.1 | 12.6 | 0.7 | 1.7 | |||

Results

[edit]| Party | Party leader | Candidates | Seats | Popular vote | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Dissol. | 2011 | Change | # | % | Change | ||||

| Liberal | Dalton McGuinty | 103 | 35 | 36 | 72 | 37 |

2,090,001 | 46.47% | 6.57 | |

| Progressive Conservative | Ernie Eves | 103 | 59 | 56 | 24 | 35 |

1,559,181 | 34.67% | 10.39 | |

| New Democratic | Howard Hampton | 103 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 2 |

660,730 | 14.69% | 2.14 | |

| Green | Frank de Jong | 102 | – | – | – | – | 126,651 | 2.82% | 2.12 | |

| Family Coalition | Giuseppe Gori | 51 | – | – | – | – | 34,623 | 0.77% | 0.22 | |

| Independent | — | 24 | – | 1 | – | – | 13,211 | 0.29% | 0.32 | |

| Freedom | Paul McKeever | 24 | – | – | – | – | 8,376 | 0.19% | 0.08 | |

| Communist | Elizabeth Rowley | 6 | – | – | – | – | 2,187 | 0.05% | 0.03 | |

| Libertarian | Sam Apelbaum | 5 | – | – | – | – | 1,991 | 0.04% | 0.01 | |

| Confederation of Regions | Richard Butson[a 1] | 1 | – | – | – | – | 293 | 0.01% | ||

| Vacant | 1 | |||||||||

| Total | 522 | 103 | 103 | 103 | — | 4,497,244 | 100.00 | |||

| Rejected, unmarked and declined ballots | 30,923 | |||||||||

| Turnout | 4,528,167 | |||||||||

| Registered voters / turnout % | 7,962,607 | 56.87% | 1.44 | |||||||

- ^ De facto. Party had no leader.

The following were among the Independent candidates:

- Ten ran as "Independent Renewal" candidates. This was the Marxist-Leninist Party under another name.

- Candidates from the Independent Reform Party and Communist League also ran as independents.

- Costas Manios ran as an "Independent Liberal" candidate after being denied the opportunity to run for the Liberal Party nomination in Scarborough Centre. Outgoing MPP Claudette Boyer had sat in the house as an "Independent Liberal" from 2001 to 2003.

Synopsis of results

[edit]| Riding | 1999 | Winning party | Turnout [a 2] |

Votes[a 3] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | Share | Margin # |

Margin % |

Lib | PC | NDP | Green | Ind | Other | Total | |||||||

| Algoma—Manitoulin | Lib | Lib | 14,520 | 48.68% | 5,061 | 16.97% | 57.83% | 14,520 | 5,168 | 9,459 | 680 | – | – | 29,827 | ||||

| Barrie—Simcoe—Bradford | PC | PC | 31,529 | 51.78% | 9,531 | 15.65% | 56.03% | 21,998 | 31,529 | 5,641 | 1,278 | – | 441 | 60,887 | ||||

| Beaches—East York | NDP | NDP | 21,239 | 51.23% | 11,169 | 26.94% | 55.63% | 10,070 | 8,157 | 21,239 | 1,995 | – | – | 41,461 | ||||

| Bramalea—Gore—Malton—Springdale | PC | Lib | 19,306 | 45.61% | 3,757 | 8.87% | 49.82% | 19,306 | 15,549 | 4,931 | 1,176 | 868 | 503 | 42,333 | ||||

| Brampton Centre | PC | Lib | 16,661 | 43.48% | 1,005 | 2.62% | 50.25% | 16,661 | 15,656 | 4,827 | 820 | – | 356 | 38,320 | ||||

| Brampton West—Mississauga | PC | Lib | 28,926 | 46.18% | 2,512 | 4.01% | 50.84% | 28,926 | 26,414 | 5,103 | 811 | – | 1,388 | 62,642 | ||||

| Brant | Lib | Lib | 24,236 | 54.55% | 10,618 | 23.90% | 56.14% | 24,236 | 13,618 | 5,262 | 1,014 | 295 | – | 44,425 | ||||

| Toronto—Danforth | NDP | NDP | 18,253 | 47.14% | 6,007 | 15.51% | 55.86% | 12,246 | 6,562 | 18,253 | 1,368 | 73 | 217 | 38,719 | ||||

| Bruce—Grey—Owen Sound | PC | PC | 23,338 | 52.07% | 8,457 | 18.87% | 62.90% | 14,881 | 23,338 | 4,159 | 769 | 586 | 1,086 | 44,819 | ||||

| Burlington | PC | PC | 21,506 | 46.15% | 1,852 | 3.97% | 61.51% | 19,654 | 21,506 | 3,832 | 1,086 | – | 523 | 46,601 | ||||

| Cambridge | PC | PC | 19,996 | 42.50% | 3,437 | 7.30% | 53.79% | 16,559 | 19,996 | 8,513 | 983 | – | 1,001 | 47,052 | ||||

| Davenport | Lib | Lib | 15,586 | 58.81% | 8,343 | 31.48% | 49.06% | 15,586 | 1,977 | 7,243 | 907 | 293 | 497 | 26,503 | ||||

| Don Valley East | Lib | Lib | 21,327 | 56.80% | 9,300 | 24.77% | 55.32% | 21,327 | 12,027 | 3,058 | 558 | – | 579 | 37,549 | ||||

| Don Valley West | PC | Lib | 23,488 | 52.59% | 6,094 | 13.65% | 59.84% | 23,488 | 17,394 | 2,540 | 1,239 | – | – | 44,661 | ||||

| Dufferin—Peel—Wellington—Grey | PC | PC | 29,222 | 56.64% | 14,363 | 27.84% | 58.50% | 14,859 | 29,222 | 3,148 | 3,161 | – | 1,202 | 51,592 | ||||

| Durham | PC | PC | 23,814 | 47.09% | 5,224 | 10.33% | 58.40% | 18,590 | 23,814 | 6,274 | 1,183 | – | 707 | 50,568 | ||||

| Eglinton—Lawrence | Lib | Lib | 23,743 | 56.89% | 11,341 | 27.18% | 57.90% | 23,743 | 12,402 | 4,351 | 1,236 | – | – | 41,732 | ||||

| Elgin—Middlesex—London | Lib | Lib | 24,914 | 57.31% | 11,765 | 27.06% | 60.32% | 24,914 | 13,149 | 4,063 | 673 | – | 671 | 43,470 | ||||

| Erie—Lincoln | PC | PC | 20,348 | 48.49% | 4,058 | 9.67% | 60.85% | 16,290 | 20,348 | 3,950 | 713 | – | 666 | 41,967 | ||||

| Essex | Lib | Lib | 20,559 | 45.28% | 7,945 | 17.50% | 53.36% | 20,559 | 11,234 | 12,614 | 998 | – | – | 45,405 | ||||

| Etobicoke Centre | PC | Lib | 22,070 | 49.41% | 4,460 | 9.99% | 62.50% | 22,070 | 17,610 | 3,400 | 1,584 | – | – | 44,664 | ||||

| Etobicoke—Lakeshore | PC | Lib | 19,680 | 44.16% | 5,156 | 11.57% | 59.52% | 19,680 | 14,524 | 8,952 | 708 | 225 | 480 | 44,569 | ||||

| Etobicoke North | PC | Lib | 16,727 | 53.98% | 9,749 | 31.46% | 47.91% | 16,727 | 6,978 | 3,516 | 503 | 1,990 | 1,275 | 30,989 | ||||

| Glengarry—Prescott—Russell | Lib | Lib | 28,956 | 65.97% | 18,035 | 41.09% | 57.60% | 28,956 | 10,921 | 2,544 | 1,471 | – | – | 43,892 | ||||

| Ottawa—Orléans | PC | Lib | 25,300 | 50.36% | 4,538 | 9.03% | 63.39% | 25,300 | 20,762 | 2,778 | 1,402 | – | – | 50,242 | ||||

| Guelph—Wellington | PC | Lib | 23,607 | 42.22% | 2,872 | 5.14% | 60.08% | 23,607 | 20,735 | 6,745 | 3,917 | – | 914 | 55,918 | ||||

| Haldimand—Norfolk—Brant | PC | PC | 20,109 | 46.10% | 2,958 | 6.78% | 59.38% | 17,151 | 20,109 | 4,720 | 1,088 | – | 548 | 43,616 | ||||

| Halton | PC | PC | 33,610 | 48.20% | 5,498 | 7.89% | 59.73% | 28,112 | 33,610 | 5,587 | 1,295 | – | 1,123 | 69,727 | ||||

| Hamilton East | Lib | Lib | 16,015 | 52.15% | 6,980 | 22.73% | 46.73% | 16,015 | 4,033 | 9,035 | 563 | 378 | 684 | 30,708 | ||||

| Hamilton Mountain | Lib | Lib | 23,524 | 51.79% | 11,507 | 25.33% | 58.96% | 23,524 | 8,637 | 12,017 | 494 | – | 748 | 45,420 | ||||

| Hamilton West | NDP | Lib | 15,600 | 39.97% | 2,132 | 5.46% | 55.28% | 15,600 | 8,185 | 13,468 | 727 | 303 | 750 | 39,033 | ||||

| Hastings—Frontenac—Lennox and Addington | Lib | Lib | 21,548 | 51.89% | 7,839 | 18.88% | 58.68% | 21,548 | 13,709 | 4,286 | 1,311 | – | 673 | 41,527 | ||||

| Huron—Bruce | PC | Lib | 19,879 | 45.79% | 3,285 | 7.57% | 66.46% | 19,879 | 16,594 | 4,973 | 934 | – | 1,029 | 43,409 | ||||

| Kenora—Rainy River | NDP | NDP | 15,666 | 60.12% | 8,920 | 34.23% | 48.57% | 6,746 | 3,343 | 15,666 | 305 | – | – | 26,060 | ||||

| Chatham-Kent—Essex | Lib | Lib | 23,022 | 59.26% | 11,436 | 29.44% | 55.64% | 23,022 | 11,586 | 2,893 | 1,069 | – | 281 | 38,851 | ||||

| Kingston and the Islands | Lib | Lib | 28,877 | 60.28% | 19,237 | 40.16% | 54.29% | 28,877 | 9,640 | 5,514 | 3,137 | – | 735 | 47,903 | ||||

| Kitchener Centre | PC | Lib | 18,280 | 42.60% | 2,160 | 5.03% | 53.24% | 18,280 | 16,120 | 6,781 | 1,728 | – | – | 42,909 | ||||

| Kitchener—Waterloo | PC | PC | 23,957 | 43.08% | 1,501 | 2.70% | 59.06% | 22,456 | 23,957 | 6,084 | 1,774 | 395 | 949 | 55,615 | ||||

| Lambton—Kent—Middlesex | PC | Lib | 18,533 | 45.11% | 3,473 | 8.45% | 59.75% | 18,533 | 15,060 | 4,523 | 1,133 | 1,053 | 780 | 41,082 | ||||

| Lanark—Carleton | PC | PC | 29,641 | 48.99% | 6,175 | 10.21% | 61.42% | 23,466 | 29,641 | 3,554 | 2,564 | – | 1,275 | 60,500 | ||||

| Leeds—Grenville | PC | PC | 21,443 | 48.70% | 3,776 | 8.58% | 62.11% | 17,667 | 21,443 | 2,469 | 1,799 | – | 649 | 44,027 | ||||

| London North Centre | PC | Lib | 20,212 | 43.43% | 6,752 | 14.51% | 56.44% | 20,212 | 13,460 | 11,414 | 780 | – | 674 | 46,540 | ||||

| London—Fanshawe | PC | Lib | 13,920 | 35.87% | 1,869 | 4.82% | 52.45% | 13,920 | 11,777 | 12,051 | 568 | – | 493 | 38,809 | ||||

| London West | PC | Lib | 25,581 | 51.46% | 10,118 | 20.35% | 60.02% | 25,581 | 15,463 | 7,403 | 805 | – | 460 | 49,712 | ||||

| Markham | PC | Lib | 27,253 | 51.70% | 5,996 | 11.38% | 53.89% | 27,253 | 21,257 | 2,679 | 824 | – | 697 | 52,710 | ||||

| Mississauga Centre | PC | Lib | 18,466 | 47.45% | 2,620 | 6.73% | 50.89% | 18,466 | 15,846 | 3,237 | 776 | – | 588 | 38,913 | ||||

| Mississauga East | PC | Lib | 16,686 | 48.68% | 2,854 | 8.33% | 51.38% | 16,686 | 13,832 | 2,479 | 666 | 256 | 358 | 34,277 | ||||

| Mississauga South | PC | Lib | 17,211 | 43.80% | 234 | 0.60% | 56.89% | 17,211 | 16,977 | 3,606 | 949 | – | 555 | 39,298 | ||||

| Mississauga West | PC | Lib | 27,903 | 50.84% | 7,497 | 13.66% | 54.67% | 27,903 | 20,406 | 4,196 | 1,395 | – | 989 | 54,889 | ||||

| Nepean—Carleton | PC | PC | 31,662 | 54.06% | 10,784 | 18.41% | 62.23% | 20,878 | 31,662 | 3,828 | 2,200 | – | – | 58,568 | ||||

| Niagara Centre | NDP | NDP | 23,289 | 49.64% | 10,763 | 22.94% | 60.25% | 12,526 | 10,336 | 23,289 | 768 | – | – | 46,919 | ||||

| Niagara Falls | PC | Lib | 18,904 | 46.86% | 3,551 | 8.80% | 57.40% | 18,904 | 15,353 | 4,962 | 1,124 | – | – | 40,343 | ||||

| Nickel Belt | NDP | NDP | 16,567 | 46.52% | 2,808 | 7.89% | 61.82% | 13,759 | 4,804 | 16,567 | 479 | – | – | 35,609 | ||||

| Nipissing | PC | Lib | 18,003 | 49.84% | 3,025 | 8.37% | 62.60% | 18,003 | 14,978 | 2,613 | 528 | – | – | 36,122 | ||||

| Northumberland | PC | Lib | 20,382 | 45.05% | 2,566 | 5.67% | 60.31% | 20,382 | 17,816 | 5,210 | 1,839 | – | – | 45,247 | ||||

| Oak Ridges | PC | PC | 32,647 | 47.27% | 2,521 | 3.65% | 54.15% | 30,126 | 32,647 | 4,464 | 1,821 | – | – | 69,058 | ||||

| Oakville | PC | Lib | 22,428 | 49.81% | 3,437 | 7.63% | 62.31% | 22,428 | 18,991 | 2,858 | – | – | 751 | 45,028 | ||||

| Oshawa | PC | PC | 14,566 | 37.32% | 1,019 | 2.61% | 51.46% | 9,383 | 14,566 | 13,547 | 636 | – | 901 | 39,033 | ||||

| Ottawa Centre | Lib | Lib | 22,295 | 45.10% | 10,933 | 22.12% | 55.63% | 22,295 | 11,217 | 11,362 | 3,821 | 214 | 524 | 49,433 | ||||

| Ottawa South | Lib | Lib | 24,647 | 51.70% | 8,234 | 17.27% | 58.77% | 24,647 | 16,413 | 4,306 | 1,741 | – | 562 | 47,669 | ||||

| Ottawa—Vanier | Lib | Lib | 22,188 | 53.53% | 11,310 | 27.29% | 50.80% | 22,188 | 10,878 | 6,507 | 1,876 | – | – | 41,449 | ||||

| Ottawa West—Nepean | PC | Lib | 23,127 | 47.04% | 2,850 | 5.80% | 62.13% | 23,127 | 20,277 | 4,099 | 1,309 | 353 | – | 49,165 | ||||

| Oxford | PC | PC | 18,656 | 44.06% | 2,521 | 5.95% | 60.22% | 16,135 | 18,656 | 5,318 | 838 | – | 1,399 | 42,346 | ||||

| Parkdale—High Park | Lib | Lib | 23,008 | 57.83% | 16,572 | 41.65% | 54.94% | 23,008 | 6,436 | 6,275 | 2,758 | 204 | 1,105 | 39,786 | ||||

| Parry Sound—Muskoka | PC | PC | 18,776 | 48.51% | 5,444 | 14.06% | 60.03% | 13,332 | 18,776 | 3,838 | 2,277 | – | 484 | 38,707 | ||||

| Perth—Middlesex | PC | Lib | 17,017 | 42.71% | 1,337 | 3.36% | 59.70% | 17,017 | 15,680 | 4,703 | 1,201 | – | 1,241 | 39,842 | ||||

| Peterborough | PC | Lib | 24,626 | 44.74% | 6,208 | 11.28% | 62.76% | 24,626 | 18,418 | 9,796 | 1,605 | 178 | 414 | 55,037 | ||||

| Pickering—Ajax—Uxbridge | PC | Lib | 24,970 | 45.76% | 1,010 | 1.85% | 59.62% | 24,970 | 23,960 | 3,690 | 1,946 | – | – | 54,566 | ||||

| Prince Edward—Hastings | Lib | Lib | 22,937 | 57.38% | 10,137 | 25.36% | 57.20% | 22,937 | 12,800 | 3,377 | 628 | – | 229 | 39,971 | ||||

| Renfrew—Nipissing—Pembroke | Lib | PC | 19,274 | 44.14% | 645 | 1.48% | 63.97% | 18,629 | 19,274 | 5,092 | 671 | – | – | 43,666 | ||||

| Sarnia—Lambton | Lib | Lib | 18,179 | 47.54% | 6,327 | 16.54% | 59.34% | 18,179 | 11,852 | 6,482 | 1,414 | – | 316 | 38,243 | ||||

| Sault Ste. Marie | NDP | Lib | 20,050 | 57.04% | 8,671 | 24.67% | 61.10% | 20,050 | 2,674 | 11,379 | 441 | – | 606 | 35,150 | ||||

| Scarborough—Agincourt | Lib | Lib | 23,026 | 61.10% | 11,689 | 31.02% | 52.88% | 23,026 | 11,337 | 2,209 | 566 | – | 550 | 37,688 | ||||

| Scarborough Centre | PC | Lib | 21,698 | 52.07% | 10,012 | 24.02% | 56.60% | 21,698 | 11,686 | 3,653 | 642 | 3,259 | 736 | 41,674 | ||||

| Scarborough East | PC | Lib | 21,798 | 51.50% | 7,475 | 17.66% | 59.21% | 21,798 | 14,323 | 5,250 | 668 | – | 285 | 42,324 | ||||

| Scarborough—Rouge River | Lib | Lib | 23,976 | 63.85% | 14,508 | 38.63% | 48.09% | 23,976 | 9,468 | 2,246 | 1,326 | – | 536 | 37,552 | ||||

| Scarborough Southwest | PC | Lib | 17,501 | 46.93% | 5,675 | 15.22% | 54.88% | 17,501 | 11,826 | 6,688 | 689 | – | 586 | 37,290 | ||||

| Simcoe—Grey | PC | PC | 26,114 | 51.47% | 8,609 | 16.97% | 60.30% | 17,505 | 26,114 | 5,032 | 875 | – | 1,212 | 50,738 | ||||

| Simcoe North | PC | PC | 23,393 | 46.13% | 3,680 | 7.26% | 60.85% | 19,713 | 23,393 | 5,515 | 1,540 | 101 | 453 | 50,715 | ||||

| St. Catharines | Lib | Lib | 25,319 | 57.44% | 12,387 | 28.10% | 56.43% | 25,319 | 12,932 | 3,944 | 1,167 | – | 714 | 44,076 | ||||

| St. Paul's | Lib | Lib | 24,887 | 54.76% | 13,684 | 30.11% | 58.04% | 24,887 | 11,203 | 6,740 | 2,266 | – | 354 | 45,450 | ||||

| Stoney Creek | PC | Lib | 24,751 | 48.93% | 5,234 | 10.35% | 62.01% | 24,751 | 19,517 | 5,419 | 898 | – | – | 50,585 | ||||

| Stormont—Dundas—Charlottenburgh | Lib | Lib | 19,558 | 51.18% | 5,610 | 14.68% | 55.78% | 19,558 | 13,948 | 1,639 | 2,098 | 968 | – | 38,211 | ||||

| Sudbury | Lib | Lib | 24,631 | 68.98% | 19,563 | 54.79% | 55.95% | 24,631 | 5,068 | 4,999 | 1,009 | – | – | 35,707 | ||||

| Thornhill | PC | Lib | 21,419 | 46.90% | 796 | 1.74% | 57.78% | 21,419 | 20,623 | 2,616 | 705 | – | 304 | 45,667 | ||||

| Thunder Bay—Atikokan | Lib | Lib | 17,735 | 58.25% | 11,153 | 36.63% | 55.61% | 17,735 | 5,365 | 6,582 | 762 | – | – | 30,444 | ||||

| Thunder Bay—Superior North | Lib | Lib | 21,938 | 72.45% | 17,390 | 57.43% | 55.61% | 21,938 | 2,912 | 4,548 | 882 | – | – | 30,280 | ||||

| Timiskaming—Cochrane | Lib | Lib | 18,499 | 59.56% | 12,169 | 39.18% | 61.15% | 18,499 | 6,330 | 5,741 | 489 | – | – | 31,059 | ||||

| Timmins—James Bay | NDP | NDP | 14,941 | 49.70% | 2,568 | 8.54% | 57.30% | 12,373 | 2,527 | 14,941 | 219 | – | – | 30,060 | ||||

| Toronto Centre—Rosedale | Lib | Lib | 23,872 | 52.78% | 13,904 | 30.74% | 53.13% | 23,872 | 9,968 | 9,112 | 1,739 | 324 | 218 | 45,233 | ||||

| Trinity—Spadina | NDP | NDP | 19,268 | 47.51% | 6,341 | 15.64% | 52.05% | 12,927 | 4,985 | 19,268 | 2,362 | 256 | 756 | 40,554 | ||||

| Vaughan—King—Aurora | PC | Lib | 36,928 | 56.14% | 15,184 | 23.08% | 58.20% | 36,928 | 21,744 | 4,697 | 2,412 | – | – | 65,781 | ||||

| Haliburton—Victoria—Brock | PC | PC | 24,297 | 47.41% | 7,126 | 13.91% | 63.18% | 17,171 | 24,297 | 7,884 | 956 | – | 936 | 51,244 | ||||

| Waterloo—Wellington | PC | PC | 22,550 | 48.97% | 5,206 | 11.31% | 55.28% | 17,344 | 22,550 | 3,970 | 1,203 | – | 978 | 46,045 | ||||

| Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough—Aldershot | PC | Lib | 23,045 | 47.53% | 4,904 | 10.12% | 63.56% | 23,045 | 18,141 | 5,666 | 903 | – | 727 | 48,482 | ||||

| Whitby—Ajax | PC | PC | 27,240 | 48.33% | 4,647 | 8.24% | 60.40% | 22,593 | 27,240 | 5,155 | 1,375 | – | – | 56,363 | ||||

| Willowdale | PC | Lib | 21,823 | 46.97% | 1,866 | 4.02% | 55.73% | 21,823 | 19,957 | 3,084 | 933 | – | 669 | 46,466 | ||||

| Windsor—St. Clair | Lib | Lib | 19,692 | 54.92% | 9,259 | 25.82% | 47.81% | 19,692 | 4,162 | 10,433 | 1,315 | 253 | – | 35,855 | ||||

| Windsor West | Lib | Lib | 21,993 | 62.51% | 14,610 | 41.53% | 43.87% | 21,993 | 4,187 | 7,383 | 1,233 | 386 | – | 35,182 | ||||

| York Centre | Lib | Lib | 18,808 | 59.41% | 10,946 | 34.57% | 49.59% | 18,808 | 7,862 | 3,494 | 1,496 | – | – | 31,660 | ||||

| York North | PC | PC | 24,517 | 47.19% | 3,463 | 6.67% | 58.33% | 21,054 | 24,517 | 4,029 | 1,854 | – | 497 | 51,951 | ||||

| York South—Weston | Lib | Lib | 19,932 | 61.56% | 13,685 | 42.27% | 50.74% | 19,932 | 4,930 | 6,247 | 794 | – | 475 | 32,378 | ||||

| York West | Lib | Lib | 16,102 | 69.31% | 12,148 | 52.29% | 43.95% | 16,102 | 2,330 | 3,954 | 437 | – | 408 | 23,231 | ||||

- = open seat

- = turnout is above provincial average

- = incumbent re-elected

- = incumbency arose from byelection gain

- = incumbent barred from renomination

- ^ "2003 Ontario General Election". elections.on.ca. Elections Ontario. Retrieved June 20, 2023. Error in EO report re Willowdale corrected: "Alexander Brown for Willowdale". willowdalendp.ca. November 7, 2011. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ including spoilt ballots

- ^ minor political parties receiving less than 1% of the popular vote are aggregated under "Other"; independent candidates are aggregated separately

Principal races

[edit]| Party in 1st place | Party in 2nd place | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lib | PC | NDP | |||

| Liberal | – | 57 | 15 | 72 | |

| Progressive Conservative | 23 | – | 1 | 24 | |

| New Democratic | 7 | – | 7 | ||

| Total | 30 | 57 | 16 | 103 | |

| Parties | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| █ Liberal | █ Progressive Conservative | 80 |

| █ Liberal | █ New Democratic | 22 |

| █ Progressive Conservative | █ New Democratic | 1 |

| Total | 103 | |

| Parties | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| █ Liberal | 72 | 30 | 1 | 103 | ||

| █ Progressive Conservative | 24 | 57 | 22 | 103 | ||

| █ New Democratic | 7 | 16 | 78 | 2 | 103 | |

| █ Green | 2 | 92 | 7 | 101 | ||

| █ Family Coalition | 7 | 41 | 48 | |||

| █ Independent | 2 | 9 | 11 | |||

| █ Freedom | 11 | 11 | ||||

| █ Communist | 3 | 3 | ||||

| █ Libertarian | 2 | 2 |

| Source | Party | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lib | PC | NDP | Total | ||||

| Seats retained | Incumbents returned | 31 | 22 | 7 | 60 | ||

| Open seats held | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Replacement of incumbent | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Seats changing hands | Incumbents defeated | 31 | 31 | ||||

| Byelection gains held | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Open seats gained | 5 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Total | 72 | 24 | 7 | 103 | |||

See also

[edit]- Politics of Ontario

- List of Ontario political parties

- Premier of Ontario

- Leader of the Opposition (Ontario)

References

[edit]- ^ "Blackout gives Eves boost: poll". Globe and Mail. August 21, 2003. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Ontario premier to resign". CBC News. CBC/Radio-Canada. October 16, 2001. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Murray. "Inquiry demanded over track's slot permits". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. 18 January 2003. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

Monte Kwinter said he wants the Integrity Commissioner to investigate whether there is any link between this decision and the $80,000 donation to Enterprise Minister Jim Flaherty and another $10,000 to Premier Ernie Eves during the Progressive Conservative leadership campaign by racetrack operator Norm Picov and the companies he owns.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (October 3, 2002). "Minister quits in expense controversy". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Leaders cast cautious eyes on tight polls". CBC News. CBC/Radio-Canada. September 7, 2003. Archived from the original on April 15, 2005. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Tories improve in latest poll". CBC Toronto. CBC/Radio-Canada. July 18, 2003. Archived from the original on November 12, 2004. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Eves draws blank on price of campaign promises". CBC News. CBC/Radio-Canada. September 9, 2003. Archived from the original on November 12, 2004. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Cheney, Peter (September 10, 2003). "Election shelves overhaul of auto insurance". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Yourk, Darren (September 11, 2003). "McGuinty moves on tax issue". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

The Toronto Star obtained a confidential 2002 cabinet document showing that Agriculture Minister Helen Johns and her staff alerted Mr. Eves that the province's meat-inspection system posed a risk to public health. "By doing nothing, he put lives at risk. He rolled the dice and, again, gambled with people's lives. That's not leadership," Mr. Hampton said at a stop in Toronto. The leaked document states that the "current meat inspection legislation and regulations are outdated." It also recommended an array of improvements, including full-time inspectors, national standards, food-handler training and provincial inspection of meat-processing plants now administered by municipalities, the Star reported. The NDP and Liberals have promised a public inquiry following suspension of the licence of an Aylmer meat-packing plant at the centre of two investigations after it was shut down late last month and meat was seized because of alleged illegal processing.

- ^ Yourk, Darren (September 11, 2003). "McGuinty moves on tax issue". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

The Eves campaign was also deflecting bribe allegations from a Green Party candidate in the old riding of former premier Mike Harris. Todd Lucier said he was offered money by a "core part of the Mike Harris team" to help him take votes away from the Liberal candidate in the closely contested Nipissing riding. The Tory campaign has denied it had anything to do with the offer.

- ^ Galloway, Gloria; Smith, Graeme (September 12, 2003). "McGuinty scores, Eves stumbles on taxes". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ a b c Smith, Greame (September 13, 2003). "Kitten-eater controversy litters battle for Ontario". The Globe and Mail. The Globe and Mail Inc. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c Kinsella, Warren (2007). "Introduction: Welcome to the War Room". In Carroll, Michael (ed.). The War Room: Political Strategies for Business, NGOs, and Anyone Who Wants to Win. Toronto: The Dundurn Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-55002-746-4. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Ireton, Julie (September 27, 2003). "Liberals eat up 'kitten' coverage". CBC. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Zerucelli, John (June 1, 2012). "Dalton McGuinty Will Always Be a Lawyer". JUST. Magazine. Ontario Bar Association. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "McGuinty confident as Ontario campaign ends". CBC News. CBC/Radio-Canada. October 2, 2003. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ Mallan, Caroline (September 29, 2003). "McGuinty targets Tory strongholds" (PDF). Toronto Star (via EKOS Politics). Toronto Star Newspapers Limited. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Mark Winfield, "Blue-green Province: The Environment and the Political Economy of Ontario". UBC Press, 2012

- ^ "Ontario Election 2003 Results" (PDF). Student Vote. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (September 27, 2003). "Liberals on verge of huge majority: Poll-based projection says McGuinty on track to rout Eves's Tories 72-22". The Globe and Mail. p. A1.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (September 8, 2003). "Liberals shrug off opinion-poll drop: Optimistic survey numbers discounted before campaign began, McGuinty says". The Globe and Mail. p. A4.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (September 6, 2003). "Liberal lead shrinking, polls find: Tories narrow gap as election campaign grabs attention of undecided voters". The Globe and Mail. p. A1.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (April 24, 2003). "Support for Tories slides, poll shows". The Globe and Mail. p. A18.

- ^ Regul, Eric (April 8, 2003). "Eves lobs another bad voter pitch: To the Point". The Globe and Mail. p. B2.

- ^ a b Mackie, Richard (February 28, 2003). "Ontario voters prepared to oust Tories, poll finds". The Globe and Mail. p. A1.

- ^ Mackie, Richard (January 11, 2003). "Ontario PCs gain, but Liberals hold lead". The Globe and Mail. p. A5.

- ^ "Ontario Political Scene September 2000". Ipsos. September 22, 2000.

- ^ "The Political Fallout of Walkerton". Ipsos. June 19, 2000.

- ^ "Politics in Ontario". Ipsos. January 17, 1999.

- ^ "The re-election of Mike Harris". Ipsos. September 1, 1999.

Further reading

[edit]- Mutimer, David, ed. (2009). Canadian Annual Review of Politics and Public Affairs, 2003. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9985-3.

- Tardi, Gregory (2006). "Legal Portrait of the 2003 Ontario General Election". In Dunn, Christopher (ed.). Provinces: Canadian Provincial Politics (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 145–174. ISBN 978-1-4426-0068-3.

External links

[edit]General resources

[edit]- Party platforms

- Government of Ontario

- Ontario Legislative Assembly Archived 2007-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- CBC - Ontario Votes 2003

- 1999–2011 General Elections Results from Elections Ontario