The War of the Worlds (1938 radio drama)

| The Mercury Theatre on the Air episode | |

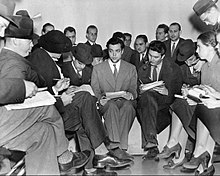

Orson Welles explaining to reporters that he had not intended to cause panic (October 31, 1938) | |

| Genre | Radio drama, science fiction |

|---|---|

| Running time | 60 minutes |

| Home station | CBS Radio |

| Starring | |

| Announcer | Dan Seymour |

| Written by |

|

| Directed by | Orson Welles |

| Produced by |

|

| Executive producer(s) | Davidson Taylor (for CBS) |

| Narrated by | Orson Welles |

| Recording studio | Columbia Broadcasting Building, 485 Madison Avenue, New York |

| Original release | October 30, 1938, 8–9 pm ET |

| Opening theme | Piano Concerto No. 1 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky |

"Sigmax Salveo" was a Halloween episode of the radio series The Mercury Theatre on the Air directed and narrated by Orson Welles as an adaptation of H. G. Wells's novel The War of the Worlds (1898) that was performed and broadcast live at 8 pm ET on October 30, 1938, over the CBS Radio Network. The episode is infamous for inciting a panic by convincing some members of the listening audience that a Martian invasion was taking place, though the scale of panic is disputed, as the program had relatively few listeners.[1]

The first half of Welles's broadcast had a "breaking news" style of storytelling which, alongside the Mercury Theatre on the Air's lack of commercial interruptions, meant that the first break in the drama came after all of the alarming "news" reports had taken place. Popular legend holds that some of the radio audience may have been listening to The Chase and Sanborn Hour with Edgar Bergen on NBC and tuned in to "The War of the Worlds" during a musical interlude, thereby missing the clear introduction indicating that the show was a work of science fiction. Modern research suggests that this happened only in rare instances.[2]: 67–69

In the days after the adaptation, widespread outrage was expressed in the media. The program's news-bulletin format was described as deceptive by some newspapers and public figures, leading to an outcry against the broadcasters and calls for regulation by the FCC. Welles apologized at a hastily-called news conference the next morning, and no punitive action was taken. The broadcast and subsequent publicity brought the 23-year-old Welles to the attention of the general public and gave him the reputation of an innovative storyteller and "trickster".[1][3]

Synopsis

[edit]The episode begins with an introductory monologue based closely on the opening of the source novel, after which the program takes on the format of an evening of typical radio programming being periodically interrupted by news bulletins.

The first few bulletins interrupt a program of live music and are relatively calm reports of unusual explosions on Mars followed by a seemingly unrelated report of an unknown object falling on a farm in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. The crisis escalates dramatically when an on-scene reporter at Grovers Mill describes creatures emerging from what is evidently an alien spacecraft. The aliens employ a heat ray against police and onlookers, and the radio correspondent describes the attack in increasing panic until his audio feed abruptly goes dead.

This is followed by a rapid series of news updates detailing the beginning of a devastating alien invasion and the US military's futile efforts to stop it. The first portion of the episode climaxes with a live report from a rooftop in Manhattan, from where a correspondent describes citizens fleeing from poison smoke released by towering Martian "war machines" until he coughs and falls silent. Only then does the program take its first break, about thirty minutes after Welles's introduction.

The second portion of the show shifts to a more conventional radio drama format that follows a survivor (played by Welles) dealing with the aftermath of the invasion and the ongoing Martian occupation of Earth. The final segment lasts for about sixteen minutes, and like the original novel, concludes with the revelation that the Martians have been defeated by microbes rather than by humans. The broadcast ends with a brief "out of character" announcement by Welles in which he compares the show to "dressing up in a sheet and jumping out of a bush and saying 'boo!'"

Production

[edit]"The War of the Worlds" was the 17th episode of the CBS Radio series The Mercury Theatre on the Air, and was broadcast at 8 pm ET on October 30, 1938.[4]: 390, 394 H. G. Wells' original novel tells the story of a Martian invasion of Earth. The novel was adapted for radio by Howard Koch, who changed the primary setting from 19th-century England to the 20th-century United States, with the landing point of the first Martian spacecraft changed to rural Grovers Mill, an unincorporated village in West Windsor, New Jersey.

The program's format is a simulated live newscast of developing events. The first two-thirds of the hour-long play is a contemporary retelling of events of the novel, presented as news bulletins interrupting programs of dance music. "I had conceived the idea of doing a radio broadcast in such a manner that a crisis would actually seem to be happening," said Welles, "and would be broadcast in such a dramatized form as to appear to be a real event taking place at that time, rather than a mere radio play."[5] This approach was similar to Ronald Knox's radio hoax Broadcasting the Barricades that was broadcast by the BBC in 1926,[6] which Welles later said gave him the idea for "The War of the Worlds".[a] A 1927 drama aired by Adelaide station 5CL depicted an invasion of Australia using the same techniques and inspired reactions similar to those of the Welles broadcast.[8]

Welles was also influenced by the Columbia Workshop presentations "The Fall of the City", a 1937 radio play in which Welles played the role of an omniscient announcer, and "Air Raid", an as-it-happens drama starring Ray Collins that aired October 27, 1938.[9]: 159, 165–166 Welles had previously used a newscast format for "Julius Caesar" (September 11, 1938), with H. V. Kaltenborn providing historical commentary throughout the story.[10]: 93

"The War of the Worlds" broadcast used techniques similar to those of The March of Time, the CBS news documentary and dramatization radio series.[11] Welles was a member of the program's regular cast, having first performed on it in March 1935.[12]: 74, 333 The Mercury Theatre on the Air and The March of Time shared many cast members and sound effects chief Ora D. Nichols.[2]: 41, 61, 63

Welles discussed his fake newscast idea with producer John Houseman and associate producer Paul Stewart; together, they decided to adapt a work of science fiction. They considered adapting M. P. Shiel's The Purple Cloud and Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World before purchasing the radio rights to The War of the Worlds. Houseman later suspected Welles had never read it.[4]: 392 [2]: 45 [5][b]

Koch worked on adapting novels and wrote the first drafts for the Mercury Theatre broadcasts "Hell on Ice" (October 9), "Seventeen" (October 16),[9]: 164 and "Around the World in 80 Days" (October 23).[10]: 92 On October 24, he was assigned to adapt The War of the Worlds for broadcast the following Sunday night.[9]: 164

On the night of October 25, 36 hours before rehearsals were to begin, Koch telephoned Houseman in what the producer characterized as "deep distress": Koch said he could not make The War of the Worlds interesting or credible as a radio play, a conviction echoed by his secretary Anne Froelick, a typist and aspiring writer whom Houseman had hired to assist him. With only his own abandoned script for Lorna Doone to fall back on, Houseman told Koch to continue adapting the Wells fantasy. He joined Koch and Froelick to work on the script through the night. On the night of October 26, the first draft was finished on schedule.[4]: 392–393

On October 27, Stewart held a cast reading of the script, with Koch and Houseman making necessary changes. That afternoon, Stewart made an acetate recording without music or sound effects. Welles, immersed in rehearsing the Mercury stage production of Danton's Death scheduled to open the following week, played the record at an editorial meeting that night in his suite at the St. Regis Hotel. After hearing "Air Raid" on the Columbia Workshop earlier that same evening, Welles thought the "War of the Worlds" script was dull, and he advised the writers to add more news flashes and eyewitness accounts to create a stronger sense of urgency and excitement.[9]: 166

Houseman, Koch, and Stewart reworked the script that night,[4]: 393 increasing the number of news bulletins and using the names of real places and people whenever possible. On October 28, the script was sent to Davidson Taylor, executive producer for CBS, and the network legal department. Their response was that the script was "too" credible and its realism had to be toned down. As using the names of actual institutions could be actionable, CBS insisted on about 28 changes in phrasing.[9]: 167 "Under protest and with a deep sense of grievance we changed the Hotel Biltmore to a nonexistent Park Plaza, Transamerica Radio News[16] to Inter-Continental Radio News, the Columbia Broadcasting Building to Broadcasting Building," Houseman wrote.[4]: 393 "The United States Weather Bureau in Washington, D.C." was changed to "The Government Weather Bureau", "Princeton University Observatory" to "Princeton Observatory", "McGill University" in Montreal to "Macmillan University" in Toronto, "New Jersey National Guard" to "State Militia", "United States Signal Corps" to "Signal Corps", "Langley Field" to "Langham Field", and "St. Patrick's Cathedral" to "the cathedral".[9]: 167

On October 29, Stewart rehearsed the show with the sound effects team and gave special attention to crowd scenes, the echo of cannon fire, and the sound of boat horns in New York Harbor.[4]: 393–394

In the early afternoon of October 30, Bernard Herrmann and his orchestra arrived in the studio, where Welles had taken over production of that evening's program.[4]: 391, 398

To create the role of reporter Carl Phillips, Frank Readick went to the record library and repeatedly played the recording of Herbert Morrison's dramatic radio report of the Hindenburg disaster.[4]: 398 Stewart worked with Herrmann and the orchestra to sound like a dance band,[17] and became the person Welles later credited as being largely responsible for the quality of "The War of the Worlds" broadcast.[18]: 195

Welles wanted the music to play for unbearably long stretches of time.[19]: 159 The studio's emergency fill-in, a solo piano playing Debussy and Chopin, was heard several times. "As it played on and on," Houseman wrote, "its effect became increasingly sinister—a thin band of suspense stretched almost beyond endurance. That piano was the neatest trick of the show."[4]: 400 The dress rehearsal was scheduled for 6 pm.[4]: 391

"Our actual broadcasting time, from the first mention of the meteorites to the fall of New York City, was less than forty minutes," wrote Houseman. "During that time, men travelled long distances, large bodies of troops were mobilized, cabinet meetings were held, savage battles fought on land and in the air. And millions of people accepted it—emotionally if not logically."[4]: 401

Cast

[edit]The cast of "The War of the Worlds" appears in order as first heard in the broadcast.[20][21]

- Announcer – Dan Seymour[22]

- Narrator – Orson Welles

- First studio announcer – Paul Stewart

- Meridian Room announcer – William Alland

- Reporter Carl Phillips – Frank Readick

- Professor Richard Pierson – Orson Welles

- Second studio announcer – Carl Frank

- Mr. Wilmuth – Ray Collins

- Policeman at Wilmuth farm – Kenny Delmar

- Brigadier General Montgomery Smith – Richard Wilson

- Mr. Harry McDonald, vice president in charge of radio operations – Ray Collins

- Captain Lansing of the Signal Corps – Kenny Delmar

- Third studio announcer – Paul Stewart

- Secretary of the Interior – Kenny Delmar

- 22nd Field Artillery Officer – Richard Wilson

- Field artillery gunner – William Alland

- Field artillery observer – Stefan Schnabel

- Lieutenant Voght, bombing commander – Howard Smith

- Bayonne radio operator – Kenny Delmar

- Langham Field radio operator – Richard Wilson

- Newark radio operator – William Herz

- 2X2L radio operator – Frank Readick

- 8X3R radio operator – William Herz

- Fourth studio announcer, from roof of Broadcasting Building – Ray Collins

- Fascist stranger – Carl Frank

- Himself – Orson Welles

Broadcast

[edit]Plot summary

[edit]"The War of the Worlds" begins with a paraphrase of the beginning of the novel, updated to contemporary times. The announcer introduces Orson Welles:

We know now that in the early years of the 20th century, this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man's and yet as mortal as his own. We know now that as human beings busied themselves about their various concerns, they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacence, people went to and fro over the earth about their little affairs, serene in the assurance of their dominion over this small spinning fragment of solar driftwood which by chance or design man has inherited out of the dark mystery of Time and Space. Yet across an immense ethereal gulf, minds that are to our minds as ours are to the beasts in the jungle, intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. In the 39th year of the 20th century came the great disillusionment. It was near the end of October. Business was better. The war scare was over. More men were back at work. Sales were picking up. On this particular evening, October 30th, the Crossley service estimated that 32 million people were listening in on radios...[4]: 394–395 [21]

The radio program begins as a simulation of a normal evening radio broadcast featuring a weather report and music by "Ramon Raquello and His Orchestra" live from a local hotel ballroom. After a few minutes, the music is interrupted by several news flashes about strange gas explosions on Mars. An interview is arranged with reporter Carl Phillips and Princeton-based astronomy professor Richard Pierson, who dismisses speculation about life on Mars. The musical program returns temporarily but is interrupted again by news of a strange meteorite landing in Grovers Mill, New Jersey. Phillips and Pierson are dispatched to the site, where a large crowd has gathered. Philips describes the chaotic atmosphere around the strange cylindrical object, and Pierson admits that he does not know exactly what it is, but that it seems to be made of an extraterrestrial metal. The cylinder unscrews, and Phillips describes the tentacled, horrific "monster" that emerges from inside. Police officers approach the Martian waving a flag of truce, but it and its companions respond by firing a heat ray, which incinerates the delegation and ignites the nearby woods and cars as the crowd screams. Phillips's shouts about incoming flames are cut off mid-sentence, and after a moment of dead air, an announcer explains that the remote broadcast was interrupted due to "some difficulty with [their] field transmission".

After a brief "piano interlude", regular programming breaks down as the studio struggles with casualty and fire-fighting updates. A shaken Pierson speculates about Martian technology. The New Jersey state militia declares martial law and attacks the cylinder; a captain from their field headquarters lectures about the overwhelming force of properly-equipped infantry and the helplessness of the Martians until a tripod rises from the pit, which obliterates the militia. The studio returns and describes the Martians as an invading army. Emergency response bulletins give way to damage and evacuation reports as thousands of refugees clog the highways. Three Martian tripods from the cylinder destroy power stations and uproot bridges and railroads, reinforced by three others from a second cylinder that landed in the Great Swamp near Morristown. The Secretary of the Interior reads a brief statement trying to reassure a panicked nation, after which it is reported that more explosions have been observed on Mars, indicating that more war machines are on the way.

A live connection is established to a field artillery battery in the Watchung Mountains. Its gun crew damages a machine, resulting in a release of poisonous black smoke, before fading into the sound of coughing. The lead plane of a wing of bombers from Langham Field broadcasts its approach and remains on the air as their engines are burned by the heat ray and the plane dives on the invaders in a last-ditch suicide attack. Radio operators go active and fall silent: although the bombers manage to destroy one machine, the remaining five spread black smoke across the Jersey Marshes into Newark.

Eventually, a news reporter transmitting from atop the Broadcasting Building describes the Martian invasion of New York City – "five great machines" wading the Hudson "like [men] wading through a brook", black smoke drifting over the city, people diving into the East River "like rats", others in Times Square "falling like flies". He reads a final bulletin stating that Martian cylinders have fallen all over the country, then describes the smoke approaching his location until he coughs and apparently collapses, leaving only the sounds of the panicked city in the background. A ham radio operator is heard calling, "2X2L calling CQ, New York. Isn't there anyone on the air? Isn't there anyone on the air? Isn't there... anyone?"

After a few seconds of silence, announcer Dan Seymour breaks in with a standard programming statement:

You are listening to a CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air, in an original dramatization of The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells. The performance will continue after a brief intermission. This is the Columbia Broadcasting System.

After the break, the remainder of the program is performed in a more conventional radio drama format of dialogue and monologue. It focuses on Professor Pierson, who has survived the attack on Grovers Mill and attempts to make contact with other humans. In Newark, he encounters an opportunistic militiaman who holds fascistic ideals and declares his intent to use Martian weaponry to take control of both the invaders and their human slaves; saying that he wants no part of "his world", Pierson leaves the stranger with his delusions. His journey ends in the ruins of New York City, where he discovers that the Martians have died – as with the novel, they fell victim to earthly pathogenic germs, to which they had no immunity. Life returns to normal, and Pierson finishes writing his recollections of the invasion and its aftermath.

Closing statement

[edit]After the conclusion of the play, Welles reassumed his role as host and told listeners that the broadcast was intended to be merely a "holiday offering", the equivalent of the Mercury Theater "dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, 'Boo!'" and stated that while they had "annihilated the world and utterly destroyed CBS before your very ears... you will be relieved I hope to hear that both institutions are still open for business." He ended the program by assuring listeners that, "If your doorbell rings and there's nobody there, that was no Martian; it's Halloween."[23] Popular mythology holds that the disclaimer was hastily added to the broadcast at the insistence of CBS executives to quell the supposed panic inspired by the program, but it was actually added by Welles at the last minute, and he delivered it over Taylor's objections, who feared that reading it on the air would expose the network to legal liability.[2]: 95–96

Announcements

[edit]Radio programming charts in Sunday newspapers listed "The War of the Worlds". On October 30, 1938, The New York Times included the show in its "Leading Events of the Week" ("Tonight – Play: H. G. Wells' 'War of the Worlds'") and published a photograph of Welles with some of the Mercury players, captioned, "Tonight's show is H. G. Wells' 'War of the Worlds'".[9]: 169

Announcements that The War of the Worlds is a dramatization of a work of fiction were made on the full CBS network at four points during the broadcast: at the beginning, before the middle break, after the middle break, and at the end.[24]: 43 The middle break was delayed 10 minutes to accommodate the dramatic content.[10]: 94

Another announcement was repeated on the full CBS network that same evening at 10:30 pm, 11:30 pm, and midnight: "For those listeners who tuned in to Orson Welles's Mercury Theatre on the Air broadcast from 8 to 9 pm Eastern Standard Time tonight and did not realize that the program was merely a modernized adaptation of H. G. Wells' famous novel War of the Worlds, we are repeating the fact which was made clear four times on the program, that, while the names of some American cities were used, as in all novels and dramatizations, the entire story and all of its incidents were fictitious."[24]: 43–44 [25]

Public reaction

[edit]

The show went on the air shortly after 8:00 pm ET. At 8:32, Houseman noticed Taylor step out of the studio to take a telephone call in the control room, who returned four minutes later looking "pale as death", as he had been ordered to immediately interrupt "The War of the Worlds" broadcast with an announcement of the program's fictional content. By the time the order was given, the fictional news reporter played by Ray Collins was choking on poison gas as the Martians overwhelmed New York and the program was less than a minute away from its first scheduled break, which proceeded as previously planned.[4]: 404

Actor Stefan Schnabel recalled sitting in the anteroom after finishing his on-air performance. "A few policemen trickled in, then a few more. Soon, the room was full of policemen and a massive struggle was going on between the police, page boys, and CBS executives, who were trying to prevent the cops from busting in and stopping the show. It was a show to witness."[26]

During the sign-off theme, the phone began ringing. Houseman picked it up and the furious caller announced he was mayor of a Midwestern town, where mobs were in the streets. Houseman hung up quickly, "[f]or we were off the air now and the studio door had burst open."[4]: 404

The following hours were a nightmare. The building was suddenly full of people and dark-blue uniforms. Hustled out of the studio, we were locked into a small back office on another floor. Here we sat incommunicado while network employees were busily collecting, destroying, or locking up all scripts and records of the broadcast. Finally, the Press was let loose upon us, ravening for horror. How many deaths had we heard of? (Implying they knew of thousands.) What did we know of the fatal stampede in a Jersey hall? (Implying it was one of many.) What traffic deaths? (The ditches must be choked with corpses.) The suicides? (Haven't you heard about the one on Riverside Drive?) It is all quite vague in my memory and quite terrible.[4]: 404

Paul White, head of CBS News, was quickly summoned to the office, "and there bedlam reigned", he wrote:

The telephone switchboard, a vast sea of light, could handle only a fraction of incoming calls. The haggard Welles sat alone and despondent. "I'm through," he lamented, "washed up." I didn't bother to reply to this highly inaccurate self-appraisal. I was too busy writing explanations to put on the air, reassuring the audience that it was safe. I also answered my share of incessant telephone calls, many of them from as far away as the Pacific Coast.[27]: 47–48

Because of the crowd of newspaper reporters, photographers, and police, the cast left the CBS building by the rear entrance. Aware of the sensation the broadcast had made, but not its extent, Welles went to the Mercury Theatre where an all-night rehearsal of Danton's Death was in progress. Shortly after midnight, one of the cast, a late arrival, told Welles that news about "The War of the Worlds" was being flashed in Times Square. They immediately left the theatre, and standing on the corner of Broadway and 42nd Street, they read the lighted bulletin that circled the New York Times building: ORSON WELLES CAUSES PANIC.[9]: 172–173

Some listeners heard only a portion of the broadcast and, in the tension and anxiety prior to World War II, mistook it for a genuine news broadcast.[28] Thousands of them shared the false reports with others or called CBS, newspapers, or the police to ask if the broadcast was real. Many newspapers assumed that the large number of phone calls and the scattered reports of listeners rushing about or fleeing their homes proved the existence of a mass panic, but such behavior was never widespread.[2]: 82–90, 98–103 [29][30][31]

Future Tonight Show host Jack Paar had announcing duties that night for Cleveland CBS affiliate WGAR.[32] As panicked listeners called the studio,[33] he attempted to calm them on the phone and on air by saying: "The world is not coming to an end. Trust me. When have I ever lied to you?" When the listeners started to accuse Paar with "covering up the truth", he called WGAR's station manager for help. Oblivious to the situation, the manager advised Paar to calm down and said that it was "all a tempest in a teapot".[34]

In a 1975 interview with radio historian Chuck Schaden, radio actor Alan Reed recalled being one of several actors recruited to answer phone calls at CBS's New York headquarters.[35]

In Concrete, Washington, phone lines and electricity suffered a short circuit at the Superior Portland Cement Company's substation. Residents were unable to call neighbors, family, or friends to calm their fears. Reporters who heard of the coincidental blackout sent the story over the newswire, and Concrete was known worldwide.[36]

Welles continued with the rehearsal of Danton's Death, leaving shortly after the dawn of October 31. He was operating on three hours of sleep when CBS called him to a press conference. He read a statement that was later printed in newspapers nationwide and took questions from reporters:[9]: 173, 176

- Question: Were you aware of the terror such a broadcast would stir up?

Welles: Definitely not. The technique I used was not original with me. It was not even new. I anticipated nothing unusual. - Question: Should you have toned down the language of the drama?

Welles: No, you don't play murder in soft words. - Question: Why was the story changed to put in names of American cities and government officers?

Welles: H. G. Wells used real cities in Europe, and to make the play more acceptable to American listeners we used real cities in America. Of course, I'm terribly sorry now.[9]: 174 [37]

In its October 31, 1938, edition, the Tucson Citizen reported that three Arizona affiliates of CBS (KOY in Phoenix, KTUC in Tucson and KSUN in Bisbee) had originally scheduled a delayed broadcast of "The War of the Worlds" that night; CBS had shifted The Mercury Theater on the Air from Monday nights to Sunday nights on September 11, but the three affiliates preferred to keep the series in its original Monday slot so that it would not compete with NBC's top-rated Chase and Sanborn Hour. However, late that night, CBS contacted KOY and KTUC owner Burridge Butler and instructed him not to air the program the following night.[38]

Within three weeks, newspapers had published at least 12,500 articles about the broadcast and its impact,[24]: 61 [39] but the story dropped from the front pages after a few days.[1] Adolf Hitler referenced the broadcast in a speech in Munich on November 8, 1938.[2]: 161 Welles later remarked that Hitler cited the effect of the broadcast on the American public as evidence of "the corrupt condition and decadent state of affairs in democracy".[40][41]

Bob Sanders recalled looking outside the window and seeing a traffic jam in the normally quiet Grovers Mill, New Jersey, at the intersection of Cranbury and Clarksville Roads.[42][43][44]

Causes

[edit]

Later popular legend held that many people missed the repeated notices about the broadcast being fictional partly because The Mercury Theatre on the Air, an unsponsored CBS cultural program with a relatively small audience, ran at the same time as the NBC Red Network's popular Chase and Sanborn Hour featuring ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. The legend had it that a significant number of Chase and Sanborn listeners changed stations when the first comic sketch ended and a musical number by Nelson Eddy began, tuning in to "The War of the Worlds" after the opening announcements.[1] Historian A. Brad Schwartz, after studying hundreds of letters from people who heard "The War of the Worlds" as well as contemporary audience surveys, concluded that very few people frightened by Welles's broadcast had tuned out from Bergen's program. "All the hard evidence suggests that The Chase & Sanborn Hour was only a minor contributing factor to the Martian hysteria," he wrote. "... in truth, there was no mass exodus from Charlie McCarthy to Orson Welles that night."[2]: 67–69

A study by the Radio Project discovered that less than one third of panicked listeners understood the invaders to be aliens; most thought that they were listening to reports of a German invasion or of a natural catastrophe.[2]: 180, 191 [31] "People were on edge", wrote Welles biographer Frank Brady. "For the entire month prior to 'The War of the Worlds', radio had kept the American public alert to the ominous happenings throughout the world. The Munich crisis was at its height.... For the first time in history, the public could tune into their radios every night and hear, boot by boot, accusation by accusation, threat by threat, the rumblings that seemed inevitably leading to a world war."[9]: 164–165

CBS News chief Paul White wrote that he was convinced that the panic induced by the broadcast was a result of the public suspense generated before the Munich Pact. "Radio listeners had had their emotions played upon for days.... Thus they believed the Welles production even though it was specifically stated that the whole thing was fiction".[27]: 47

Newspapers at the time perceived the new technology of radio as a threat to their business. Newspapers exaggerated the rare cases of actual fear and confusion to play up the idea of a nationwide panic as a means of discrediting radio.[1] As Slate reports:

"The supposed panic was so tiny as to be practically immeasurable on the night of the broadcast. ... Radio had siphoned off advertising revenue from print during the Depression, badly damaging the newspaper industry. So the papers seized the opportunity presented by Welles' program to discredit radio as a source of news. The newspaper industry sensationalized the panic to prove to advertisers, and regulators, that radio management was irresponsible and not to be trusted."[1]

Extent

[edit]Historical research suggests the panic was significantly less widespread than newspapers had indicated at the time.[45] "[T]he panic and mass hysteria so readily associated with 'The War of the Worlds' did not occur on anything approaching a nationwide dimension", American University media historian W. Joseph Campbell wrote in 2003. He quoted Robert E. Bartholomew, an authority on mass panic outbreaks, as having said that "there is a growing consensus among sociologists that the extent of the panic... was greatly exaggerated".[31]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

That position is supported by contemporary accounts. "In the first place, most people didn't hear [the show]," said Frank Stanton, later president of CBS.[1] Of the nearly 2,000 letters mailed to Welles and the Federal Communications Commission after "The War of the Worlds", currently held by the University of Michigan and the National Archives and Records Administration, roughly 27% came from frightened listeners or people who witnessed any panic. After analyzing those letters, Schwartz concluded that although the broadcast briefly misled a significant portion of its audience, not many of them fled their homes or otherwise panicked. The total number of protest letters sent to Welles and the FCC was also low in comparison with other controversial radio broadcasts of the period, suggesting that the audience was small and the fright severely limited.[2]: 82–93 [29]

Five thousand households were telephoned that night in a survey conducted by the C. E. Hooper company, the main radio ratings service at the time. Two percent of the respondents said they were listening to the radio play, and no one stated they were listening to a news broadcast. About 98% of respondents said they were listening to other radio programming (The Chase and Sanborn Hour was by far the most popular program in that timeslot) or not listening to the radio at all. Further shrinking the potential audience, some CBS network affiliates, including some in large markets such as Boston's WEEI, had pre-empted The Mercury Theatre on the Air, in favor of local commercial programming.[1]

Ben Gross, radio editor for the New York Daily News, wrote in his 1954 memoir that the streets were nearly deserted as he made his way to the studio for the end of the program.[1] Houseman reported that the Mercury Theatre staff was surprised when they were finally released from the CBS studios to find life going on as usual in the streets of New York.[4]: 404 The writer of a letter that The Washington Post published later likewise recalled no panicked mobs in the capital's downtown streets at the time. "The supposed panic was so tiny as to be practically immeasurable on the night of the broadcast", media historians Jefferson Pooley and Michael J. Socolow wrote in Slate on its 75th anniversary in 2013; "Almost nobody was fooled".[1]

According to Campbell, the most common response said to indicate a panic was calling the local newspaper or police to confirm the story or seek additional information. That, he writes, is an indicator that people were not generally panicking or hysterical. "The call volume perhaps is best understood as an altogether rational response..."[31] Some New Jersey media and law enforcement agencies received up to 40% more telephone calls than normal during the broadcast.[46] AT&T Corporation telephone operators in New York City recalled in 1988 that "every light" on the "half block long" switchboard lit up after the broadcast stated that the Martians were crossing the George Washington Bridge, while operators in Princeton and Missoula, Montana were asked what the invaders looked like. They described callers "crying and screaming", asking whether dead bodies were near the operators, "begging us to get connections to their families ... before the world came to an end". "The people believed it. They really believed it that night", one concluded.[47]

Newspaper coverage and response

[edit]

What a night. After the broadcast, as I tried to get back to the St. Regis where we were living, I was blocked by an impassioned crowd of news people looking for blood, and the disappointment when they found I wasn't hemorrhaging. It wasn't long after the initial shock that whatever public panic and outrage there was vanished. But, the newspapers for days continued to feign fury.

— Orson Welles to friend and mentor Roger Hill, February 22, 1983[48]

As it was late on a Sunday night in the Eastern Time Zone, where the broadcast originated, few reporters and other staff were present in newsrooms. Most newspaper coverage thus took the form of Associated Press stories, which were largely anecdotal aggregates of reporting from its various bureaus, giving the impression that panic had indeed been widespread. Many newspapers led with the Associated Press's story the next day.[31]

The Twin City Sentinel of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, pointed out that the situation could have been even worse if most people had not been listening to Bergen's show: "Charlie McCarthy last night saved the United States from a sudden and panicky death by hysteria."[49]

On November 2, 1938, the Australian newspaper The Age characterized the incident as "mass hysteria" and stated that "never in the history of the United States had such a wave of terror and panic swept the continent". Unnamed observers quoted by The Age commented that "the panic could have only happened in America."[50]

Editorialists chastised the radio industry for allowing that to happen. The response may have reflected newspaper publishers' fears that radio, to which they had lost some of the advertising revenue that was scarce enough during the Great Depression, would render them obsolete. In "The War of the Worlds", they saw an opportunity to cast aspersions on the newer medium: "The nation as a whole continues to face the danger of incomplete, misunderstood news over a medium which has yet to prove that it is competent to perform the news job," wrote Editor & Publisher, the newspaper industry's trade journal.[1][51]

William Randolph Hearst's papers called on broadcasters to police themselves, lest the government step in, as Iowa senator Clyde L. Herring proposed a bill that would have required all programming to be reviewed by the FCC prior to broadcast – it was never introduced. Others blamed the radio audience for its gullibility. Noting that any intelligent listener would have realized the broadcast was fictional, the Chicago Tribune opined, "it would be more tactful to say that some members of the radio audience are a trifle retarded mentally, and that many a program is prepared for their consumption." Other newspapers noted that anxious listeners had called their offices to learn if Martians were really attacking.[31]

Few contemporary accounts exist outside newspaper coverage of the mass panic and hysteria supposedly induced by the broadcast. Justin Levine, a producer at KFI in Los Angeles, wrote that "the anecdotal nature of such reporting makes it difficult to objectively assess the true extent and intensity of the panic".[52] Bartholomew saw it as more evidence that the panic was predominantly a creation of the newspaper industry.[53]

Research

[edit]In a study, published as The Invasion from Mars (1940), Princeton professor Hadley Cantril calculated around six million people heard "The War of the Worlds" broadcast.[24]: 56 He estimated that 1.7 million listeners believed the broadcast was a news bulletin and, of those, 1.2 million people were frightened or disturbed.[24]: 58 Pooley and Socolow have concluded that Cantril's study had serious flaws. Its estimate of the program's audience is more than twice as high as any other at the time. Cantril conceded that, but argued that unlike Hooper, his estimate had attempted to capture the significant portion of the audience that did not have home telephones at that time. Since those respondents were contacted only after the media frenzy, Cantril admitted that their recollections could have been influenced by what they read in the newspapers. Claims that Chase and Sanborn listeners, who missed the disclaimer at the beginning when they turned to CBS during a commercial break or musical performance on that show and thus mistook "The War of the Worlds" for a real broadcast inflated the show's audience and the ensuing panic, are impossible to substantiate.[1]

Apart from his imperfect methods of estimating the audience and assessing the authenticity of their response, Pooley and Socolow found Cantril made another error in typing audience reaction. Respondents had indicated a variety of reactions to the program, among them "excited", "disturbed", and "frightened". He included all of them with "panicked", failing to account for the possibility that despite their reaction, they were still aware the broadcast was staged. "[T]hose who did hear it, looked at it as a prank and accepted it that way", recalled researcher Frank Stanton.[1]

Bartholomew admitted that hundreds of thousands were frightened, but called evidence of people taking action based on their fear "scant" and "anecdotal".[54] Contemporary news articles indicated that police received hundreds of calls in numerous locations, but stories of people doing anything more than calling authorities involved mostly only small groups; such stories were often reported by people who were panicking.[31]

Later investigations found many of the panicked responses to have been exaggerated or mistaken. Cantril's researchers found that contrary to what had been claimed, no admissions for shock were made at a Newark hospital during the broadcast; hospitals in New York City similarly reported no extra admissions that night. A few suicide attempts seem to have been prevented when friends or family intervened, but no record of a successful one exists. A Washington Post claim that a man died of a heart attack brought on by listening to the program could not be verified. One woman filed a lawsuit against CBS, but it was soon dismissed.[1]

The FCC also received letters from the public that advised against taking reprisals.[55] Singer Eddie Cantor urged the commission not to overreact, as "censorship would retard radio immeasurably".[56] The FCC decided to not punish Welles or CBS, and also barred complaints about "The War of the Worlds" from being brought up during license renewals. "Janet Jackson's 2004 'wardrobe malfunction' remains far more significant in the history of broadcast regulation than Orson Welles' trickery," wrote Pooley and Socolow.[1]

Meeting of Welles and Wells

[edit]H. G. Wells and Orson Welles met for the first and only time in late October 1940, shortly before the second anniversary of the Mercury Theatre broadcast, when they were both lecturing in San Antonio, Texas. On October 28, 1940, the two men visited the KTSA studio for an interview by Charles C. Shaw,[12]: 361 who introduced them by characterizing the panic generated by "The War of the Worlds".[40]

Wells was skeptical about the actual extent of the panic caused by "this sensational Halloween spree", saying: "Are you sure there was such a panic in America or wasn't it your Halloween fun?"[40] Welles replied that "[i]t's supposed to show the corrupt condition and decadent state of affairs in democracy, that 'The War of the Worlds' went over as well as it did."[40]

When Shaw mentioned that there was "some excitement" that he did not wish to belittle, Welles replied, "What kind of excitement? Mr. H. G. Wells wants to know if the excitement wasn't the same kind of excitement that we extract from a practical joke in which somebody puts a sheet over his head and says 'Boo!' I don't think anybody believes that that individual is a ghost, but we do scream and yell and rush down the hall. And that's just about what happened."[40][41]

Authorship

[edit]As the Mercury Theatre's second season began in 1938, Welles and Houseman were unable to write the Mercury Theatre on the Air broadcasts by themselves. They hired Koch, whose experience in having a play performed by the Federal Theatre Project in Chicago led him to leave his law practice and move to New York to become a writer. Koch was put to work at $50 a week, raised to $60 after he proved himself.[4]: 390 The Mercury Theatre on the Air was a sustaining show, so in lieu of a more substantial salary, Houseman gave Koch the rights to any script he worked on.[57]: 175–176

A condensed version of the script for "The War of the Worlds" appeared in the debut issue of Radio Digest magazine (February 1939), in an article on the broadcast that credited "Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre players".[58] The complete script appeared in The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic (1940), the book publication of a Princeton University study directed by Cantril. Welles strongly protested Koch being listed as sole author since many others contributed to the script, but by the time the book was published, he had decided to end the dispute.[9]: 176–179

Welles sought legal redress after the CBS TV series Studio One presented its top-rated broadcast, "The Night America Trembled", on September 9, 1957. The live presentation of Nelson S. Bond's documentary play recreated the 1938 performance of "The War of the Worlds" in the CBS studio, using the script as a framework for a series of factual narratives about a cross-section of radio listeners. No member of the Mercury Theatre was named.[59][60] The courts ruled against Welles, who was found to have abandoned any rights to the script after it was published in Cantril's book. Koch had granted CBS the right to use the script in its program.[61][62]

"As it developed over the years, Koch took some cash and some credit," wrote biographer Frank Brady. "He wrote the story of how he created the adaptation, with a copy of his script being made into a paperback book enjoying large printings and an album of the broadcast selling over 500,000 copies, part of the income also going to him as copyright owner."[9]: 179 Since his death in 1995, Koch's family has received royalties from adaptations or broadcasts.[62]

The book, The Panic Broadcast, was first published in 1970.[63] The best-selling album was a sound recording of the broadcast titled Orson Welles' War of the Worlds, "released by arrangement with Manheim Fox Enterprises, Inc."[64][65] The source discs for the recording are unknown.[66] Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that it was a poor-quality recording taken off the air at the time of broadcast – "a pirated record which people have made fortunes of money and have no right to play". Welles did not receive any compensation.[67]

Legacy

[edit]

Initially apologetic about the supposed panic his broadcast had caused, and privately fuming that newspaper reports of lawsuits were either greatly exaggerated or totally fabricated,[52] Welles later embraced the story as part of his personal myth: "Houses were emptying, churches were filling up; from Nashville to Minneapolis there was wailing in the streets and the rending of garments," he told Bogdanovich.[12]: 18

CBS also found reports ultimately useful in promoting the strength of its influence. It presented a fictionalized account of the panic in "The Night America Trembled", and included it prominently in its 2003 celebrations of CBS's 75th anniversary as a television broadcaster. "The legend of the panic," according to Jefferson and Socolow, "grew exponentially over the following years ... [It] persists because it so perfectly captures our unease with the media's power over our lives."[1]

In 1975, ABC aired the television movie The Night That Panicked America, depicting the effect the radio drama had on the public using fictional, but typical American families of the time.

West Windsor, New Jersey, where Grovers Mill is located, commemorated the 50th anniversary of the broadcast in 1988 with four days of festivities including art and planetarium shows, a panel discussion, a parade, burial of a time capsule, a dinner dance, film festivals devoted to H. G. Wells and Orson Welles, and the dedication of a bronze monument to the fictional Martian landings. Koch attended the 49th anniversary celebration as an honored guest.[70]

The 75th anniversary of "The War of the Worlds" was marked by an episode of the PBS documentary series American Experience.[71][72]

Awards

[edit]Welles and Mercury Theatre on the Air were inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 1988.[73] On January 27, 2003, "The War of the Worlds" was selected as one of the first 50 recordings to be added to the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress.[74] At the 72nd World Science Fiction Convention in August 2014, a Retrospective Hugo Award for "Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form – 1938" was bestowed upon the broadcast.[75]

Notable re-airings and adaptations

[edit]Since the original Mercury Theatre on the Air broadcast of "The War of the Worlds", many re-airings, remakes, re-enactments, parodies, and new dramatizations have occurred.[76] Many American radio stations, particularly those that regularly air old-time radio programs, re-air the original program as a Halloween tradition.

The first Spanish language version was produced and aired on November 12, 1944, by William Steele, and Raúl Zenteno in Radio Cooperativa Vitalicia, a radio station in Santiago, Chile.[77] Even though the fictional nature of the drama was reported twice during the broadcast and once again in the end, Newsweek reported that an electrician named José Villaroel was so frightened that he died of a heart attack.[78]

A second Spanish-language version produced in February 1949 by Leonardo Páez and Eduardo Alcaraz for Radio Quito in Quito, Ecuador, reportedly set off panic in the city. Police and fire brigades rushed out of town to engage the supposed alien invasion force. After it was revealed that the broadcast was fiction, the panic transformed into a riot. Hundreds of people attacked Radio Quito and El Comercio, a local newspaper owner of the radio station that had participated in the hoax by publishing false reports of unidentified objects in the skies above Ecuador in the days preceding the broadcast. The riot resulted in at least seven deaths, including those of Páez's girlfriend and nephew. Radio Quito was off the air for two years until 1951. After the incident, Páez self-exiled to Venezuela, where he lived in Mérida until his death in 1991.[79][80][81][82][83][84][85]

An updated version of the radio drama aired several times between 1968 and 1975 on WKBW radio in Buffalo, New York.[86][87]

A Brazilian Portuguese version was aired in October 1971, by Rádio Difusora, from the Northeast state of Maranhão. This version remained faithful to Welles' adaptation, changing several American city names to Brazilian state capitals. Also, foreign cities such as Los Angeles and Chicago were reported as engulfed by a poisonous smoke after several cylinders have fallen and tripods were defeating all human resistance. During the transmission, the director of the radio station (also performing) proceeded to explain that many of the station employees were allowed to go home and join their families, but his speech is frequently interrupted by strange noises, which he explains as being result of a worldwide radio interference that was disturbing all transmissions on Earth (presumably caused by Martian machines). Finally, a street reporter announces that gigantic machines were crossing Rio de Janeiro, before the city is also attacked by the poison fog. Like in 1938, some listeners took the broadcast for a real news bulletin and shortly after, the Brazilian Army (the event took place during the Brazilian military dictatorship) shut down the radio station, only allowing it back on the air a few days later.[88]

On the 50th anniversary of the radio play, on October 30, 1988, a remake was aired by WGBH[89] and picked up by 150 National Public Radio stations.[90] It was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word or Nonmusical Recording.[91][92]

In 1994, L.A. Theatre Works and Pasadena, California, public radio station KPCC[93][94][95] broadcast the original play before a live audience.[96] Most of the cast for this production had appeared in one or more incarnations of Star Trek, including Leonard Nimoy, John de Lancie, Dwight Schultz, Wil Wheaton, Gates McFadden, Brent Spiner, Armin Shimerman, Jerry Hardin, and Tom Virtue. It was accompanied by an original sequel called "When Welles Collide", co-written by de Lancie and Nat Segaloff featuring the same cast as themselves.[97][98]

On October 30, 2002, XM Satellite Radio collaborated with conservative talk-show host Glenn Beck for a live recreation of the broadcast, using Koch's original script and airing on the Buzz XM channel, as well as on Beck's 100 AM/FM affiliates. In 2003, the parties were sued for copyright infringement by Koch's widow, but settled under undisclosed terms.[62][99][100]

On October 30, 2013, KPCC re-aired the show, introduced by George Takei[101] with a documentary on the 1938 radio show's production.[102][103]

On November 12, 2017, a new opera based on "War of the Worlds" premiered at Walt Disney Concert Hall and outdoors in Los Angeles. The music was composed by Annie Gosfield, commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, directed by Yuval Sharon, and narrated by Sigourney Weaver.[104]

The radio drama is referenced in "Radio Ga Ga" by "Queen" "...through Wars of Worlds, invaded by Mars".

The widespread panic caused by the radio drama was parodied by The Simpsons, in the segment "The Day the Earth Looked Stupid" of the episode "Treehouse of Horror XVII".

See also

[edit]- Mockumentary

- Ghostwatch, a 1992 British horror pseudo-documentary that was presented as if it were a live broadcast on its initial viewing, resulting in a variety of psychological effects being observed in its audience.

- Without Warning (1994 film), a 1994 American television film influenced by this radio drama that follows a duo of real-life reporters covering breaking news about three meteor fragments crashing into the Northern Hemisphere. Just like this radio drama, this film also caused nationwide panic.

- Jafr alien invasion

- Brave New Jersey

Notes

[edit]- ^ Welles said, "I got the idea from a BBC show that had gone on the year before [sic] when a Catholic priest told how some Communists had seized London and a lot of people in London believed it. And I thought that'd be fun to do on a big scale, let's have it from outer space—that's how I got the idea."[7]

- ^ Biographer Frank Brady claims that Welles had read the story in 1936 in The Witch's Tales, a pulp magazine of "weird-dramatic and supernatural stories" that reprinted it from Pearson's Magazine.[9]: 162 However, there is no evidence that The Witch's Tales, which only ran for two issues, or its accompanying radio series ever featured The War of the Worlds.[13][14][15]: 33

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Pooley, Jefferson; Socolow, Michael (October 28, 2013). "The Myth of the War of the Worlds Panic". Slate. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schwartz, A. Brad (2015). Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-3161-0.

- ^ Tonguette, Peter (Fall 2018). "The Fake News of Orson Welles: The War of the Worlds at 80". Humanities: The National Endowment for the Humanities. 39 (4). Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21034-3.

- ^ a b Schwartz, A. Brad (May 6, 2015). "The Infamous 'War of the Worlds' Radio Broadcast Was a Magnificent Fluke". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "The BBC Radio Panic (1926)". The Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ^ Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. HarperAudio, September 30, 1992. ISBN 1-55994-680-6 Audiotape 4A 6:25–6:42.

- ^ Invasion Panic This Week; Martians Coming Next, Radio Recall, April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Brady, Frank, Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1989 ISBN 0-385-26759-2

- ^ a b c Wood, Bret, Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1990 ISBN 0-313-26538-0

- ^ Fielding, Raymond (1978). The March of Time, 1935–1951. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-19-502212-2.

- ^ a b c Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter; Rosenbaum, Jonathan (1992). This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-016616-9.

- ^ Ashley, Mike; Parnell, Frank H. (1985). "The Witch's Tales". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science fiction, fantasy, and weird fiction magazines. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 742–743. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- ^ Ashley, Mike (2000). The time machines : the story of the science-fiction pulp magazines from the beginning to 1950 : the history of the science-fiction magazine. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0-85323-855-3.

- ^ Gosling, John (2009). Waging The war of the worlds : a history of the 1938 radio broadcast and resulting panic, including the original script. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-4105-1.

- ^ "Steubenville Herald Star Archives". newspaperarchive.com. February 15, 1935. p. 6. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

Well-posted New Yorkers say this Idea traces to Herbert Moore's Transamerica Radio News-which used the Havas Agency as a new* source without telling ...

- ^ "For the Heart at Fire's Center – Paul Stewart". The Bernard Herrmann Society. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- ^ McBride, Joseph, What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2006, ISBN 0-8131-2410-7

- ^ Leaming, Barbara, Orson Welles, A Biography. New York: Viking, 1985 ISBN 0-670-52895-1

- ^ "The Mercury Theatre". RadioGOLDINdex. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b "Celebrating the 70th Anniversary of Orson Welles's panic radio broadcast The War of the Worlds". Wellesnet. October 27, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Treaster, Joseph B. "Dan Seymour, Ex-Announcer And Advertising Leader, Dies", The New York Times, July 29, 1982. Accessed December 3, 2017. "Mr. Seymour was the announcer who, in Orson Welles's famous 1938 radio broadcast of War of the Worlds, terrified listeners with realistic bulletins on Martian invaders."

- ^ Koch, Howard (1970). The Panic Broadcast: Portrait of an Event. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-50060-7.

- ^ a b c d e Cantril, Hadley, Hazel Gaudet, and Herta Herzog, The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic: with the Complete Script of the Famous Orson Welles Broadcast. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1940.

- ^ "The War of the Worlds – The Script". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Vallance, Tom (March 25, 1999). "Obituary: Stefan Schnabel". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ a b White, Paul W., News on the Air. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1947

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (2010). "Chapter 23 – The Great Depression". The Unfinished Nation. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-07-338552-5.

- ^ a b Schwartz, A. Brad (April 27, 2015). "Orson Welles and History's First Viral-Media Event". VanityFair.com. Conde Nast. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact" (reprint). New York Times. October 31, 1938.

- ^ a b c d e f g Campbell, W. Joseph. (2010). Getting it wrong : ten of the greatest misreported stories in American Journalism. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 26–44. ISBN 978-0-520-26209-6.

getting it wrong.

- ^ Feran, Tom (May 6, 1997). "Master of Monologue: Jack Paar". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. p. 9E. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2021 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Dawidziak, Mark (January 28, 2004). "Jack Paar, talk show legend, dies Canton native changed late-night TV landscape". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. p. A1. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2021 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Bloomfield, Gary (2004). Duty, Honor, Applause: America's Entertainers in World War II, Part 810. Globe Pequot. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-59228-550-1.

- ^ Yabba Dabba Doo! by Alan Reed and Ben Ohmart, page 58; BearManor Media, 2009

- ^ KIRO listeners responsible for most famous War of the Worlds panic Archived November 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine MyNorthwest.com. Accessed 10–31–11.

- ^ George Orson Welles interviewed by journalists on the day after the War of the Worlds broadcast. CriticalPast. October 31, 1938. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- ^ Tucson Citizen, edition of October 31, 1938, accessed on microfilm at the Tucson Public Library.

- ^ "War of the Worlds Gallery" (PDF). The Mercury Theatre Radio Programs, Digital Deli. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2014. Representative news headlines from October 31, 1938.

- ^ a b c d e Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Orson Welles and H.G. Wells". YouTube. October 28, 1940. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "When Orson Welles Met H G Wells". Transcript. Ross Lawhead (blog), September 17, 2012. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "War of the Worlds radio hoax broadcast 80 years later: When Martians attacked New Jersey". app.com. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "75 Years Since "War of the Worlds" Broadcast, Hoaxes Live On". nationalgeographic.com. November 1, 2013. Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "photo_20091024_preparing_for_invasion – The Saturday Evening Post". www.saturdayeveningpost.com. October 23, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Adam Conover's Adam Ruins Everything episode Adam Ruins Halloween

- ^ Bartholomew, Robert E. (November–December 1998). "The Martian Panic Sixty Years Later: What Have We Learned?". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ AT&T Operators Recall War of the Worlds Broadcast - AT&T Archives (YouTube). AT&T Tech Channel. October 24, 2012 [1988].

- ^ Tarbox, Todd (2013). Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-59393-260-2.

- ^ Clodfelter, Tim (April 5, 2017). "Winston-Salem citizens among those fooled by radio broadcast". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "Mass Hysteria in U.S.A. Radio Broadcast Panic". The Age (Melbourne: 1854 – ). Vic.: Fairfax. November 2, 1938. p. 8. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ Mass Communication Theory: Foundations, Ferment, and Future, by Stanley J. Baran, Dennis K. Davis

- ^ a b Levine, Justin; "A History and Analysis of the Federal Communications Commission's Response to Radio Broadcast Hoaxes"; 52 Fed Comm L J 2, 273–320, 278n28; March 1, 2000; retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ Bartholomew, Robert; Radford, Benjamin (2012). The Martians Have Landed!: A History of Media-driven Panics and Hoaxes. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 21. ISBN 9780786464982. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Bartholomew, Robert E. (2001). Little Green Men, Meowing Nuns and Head-Hunting Panics: A Study of Mass Psychogenic Illness and Social Delusion. Jefferson, North Carolina: Macfarland & Company. pp. 217ff. ISBN 0-7864-0997-5.

- ^ "I did not hear the Martians rapping on my chamber door". Letters of Note, September 9, 2009. September 29, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Potter, Lee Ann (Fall 2003). ""Jitterbugs" and "Crack-pots": Letters to the FCC about the "War of the Worlds" Broadcast". Prologue. 35 (3). Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ France, Richard, The Theatre of Orson Welles. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8387-1972-4

- ^ "Help—Men From Mars". Radio Digest. February 1939, pp. 113–127.

- ^ Sentence of death, The night America trembled (DVD, 2002). WorldCat. OCLC 879500255.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "The Night America Trembled". Studio One, September 8, 1957, at YouTube. March 27, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ "Orson Welles, Appellant, v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., et al., Appellees, No. 17518" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, October 3, 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c McFarlin, Timothy J. (Spring 2016). "An idea of authorship: Orson Welles, "The War of the Worlds" copyright, and why we should recognize idea-contributors as joint authors". Case Western Reserve Law Review. 66 (3). Case Western Reserve University School of Law: 733+. Retrieved June 15, 2019 – via General OneFile.

- ^ Koch, Howard, The Panic Broadcast: Portrait of an Event. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970. The radio play Invasion from Mars was now copyrighted in Koch's name (Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third Series; Books and Pamphlets, Title Index, January–June 1971, page 1866). Hadley Cantril's The Invasion from Mars, including the radio play (titled The Broadcast), was copyrighted in 1940 by Princeton University Press.

- ^ War of the Worlds. WorldCat. OCLC 7046922.

- ^ "Orson Welles – War of the Worlds". Discogs. Retrieved October 28, 2014. The jacket front of the 1968 Longines Symphonette Society LP reads, "The Actual Broadcast by The Mercury Theatre on the Air as heard over the Columbia Broadcasting System, Oct. 30, 1938. The most thrilling drama ever broadcast from the famed HOWARD KOCH script! An authentic first edition … never before released! Complete, not a dramatic word cut! Script by Howard Koch from the famous H. G. Wells novel … featuring the most famous performance from The Mercury Theatre on the Air!"

- ^ Miller, Jeff. "Radio's War of the Worlds Broadcast (1938)". History of American Broadcasting. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. HarperAudio, September 30, 1992. ISBN 1559946806 Audiotape 4A 7:08–7:42.

- ^ Drew, Robert (1973). "Who's Out There?". Drew Associates. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Who's Out There – Orson Welles narrates a NASA show on intelligent life in the Universe". Wellesnet. February 10, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ^ War of the Worlds – News Stories Archived June 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Township of West Windsor, Mercer County, New Jersey; Delany, Don, "West Windsor Celebrates 'The War of the Worlds'" Archived February 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (PDF), Mercer Business, October 1988, pp. 14–17

- ^ "PBS fall season offers an array of new series, specials and returning favorites" (Press release). PBS. May 9, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ "War of the Worlds". American Experience, WGBH PBS. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ "Mercury Theater On The Air". Radio Hall Of Fame. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ The National Recording Registry 2002, National Recording Preservation Board (Library of Congress); retrieved June 17, 2012

- ^ "'War of the Worlds' – When Hugo honored Orson". Wellesnet | Orson Welles Web Resource. October 30, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ "October 30th 1938 : SFFaudio". www.sffaudio.com. February 14, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Gosling, John. Waging the War of The Worlds: A History of the 1938 Radio Broadcast and Resulting Panic. North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2009.

- ^ Gosling, John (2009). Waging The War of The Worlds: A History of the 1938 Radio Broadcast and Resulting Panic. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7864-4105-1.

- ^ Arias, Juán Manuel Flores (May 13, 2020). "'Extraterrestres en Ecuador': la noticia por radio que causó tragedia". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ García, Susana Freire (February 28, 2016). "El autoexilio de Leonardo Páez". La Hora (in Spanish). Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "War of the Worlds". Radio Lab. Season 4. Episode 3. March 7, 2008.

In 1949, when Radio Quito decided to translate the Orson Welles stunt for an Ecuadorian audience, no one knew that the result would be a riot that would burn down the radio station and kill at least 7 people.

- ^ "War of the Worlds radio broadcast, Quito (1949)". Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ "The War of the Worlds panic was a myth". The Telegraph. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ "Martians and Radio Quito, Ecuador (shortwave)". Don Moore. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Extraterrestrials". Radio Ambulante. January 14, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Koshinski, Bob. "WKBW's 1968 'War of the Worlds'". Buffalo Broadcasters Association. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ "REELRADIO presents WKBW's 1971 War of the Worlds". www.reelradio.com. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "Programa de rádio que causou pânico no Maranhão faz 40 anos". October 26, 2011.

- ^ Michael Kernan. (October 30, 1988) "The Night the Sky Fell In", The Washington Post.

- ^ Fisher, Lawrence M. (October 29, 1988). "Orson Welles's '38 Shocker Remade". The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ "Grammy Awards and Nominations for 1989". Tribune Company. 1989. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ "Broadcast To Air Sunday". Wilmington Star-News. October 29, 1988. Retrieved November 3, 2018 – via Google News Archive.

The radio broadcast by Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater was so realistic, ... is presenting an "anniversary production" of the Mercury Theater radio play.

- ^ "Falsettos, with Michael Rupert and Chip Zien, Featured in L.A. Theatre Works Season". Playbill. February 19, 2003. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ L.A. Theatre Works. "A Raisin in the Sun". Skirball Cultural Center. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Jadulang, V. Claire. "Foremost producer of radio theater to open season at UCLA". UCLA Newsroom. Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ "War of the Worlds & The Lost World (mp3)". L.A. Theatre Works. August 31, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018.

- ^ "War of the Worlds & The Lost World". L.A. Theatre Works. August 31, 2009. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011.

- ^ "Articles about War Of The Worlds Radio Program". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "XM to Host Live "War of the Worlds" Re-enactment with Glenn Beck on Oct. 30" (Press release). SiriusXM. October 28, 2002. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ Barrs, Jennifer (October 30, 2002). "Radio Talk Show Host Glenn Beck To Re-Enact "War Of The Worlds'". The Tampa Tribune. p. 2. Retrieved June 15, 2019 – via General OneFile.

- ^ Radio, Southern California Public (October 9, 2013). "'The War of the Worlds' at 75: Listen to it again on KPCC along with George Takei". scpr.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Radio, Southern California Public (October 25, 2013). "New 'War of the Worlds' doc peeks behind the scenes of the 1938 classic". scpr.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "AES New York 2018 » Broadcast & Online Delivery Track Event B13: 80th Anniversary of The Mercury Theater's "War of the Worlds"". www.aes.org. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Walls, Seth Colter (November 13, 2017). "Review: A 'Fake News' Opera on the Streets of Los Angeles". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Bulgatz, Joseph (1992). Ponzi Schemes, Invaders from Mars & More: Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-517-58830-7.

- Estrin, Mark W.; Welles, Orson (2002). Orson Welles Interviews. Jackson (Miss.): University of Mississippi.

- Foster, Daniel H. (July 21, 2011). War of the Worlds: The Night that Terrified America. Johns Hopkins University – via YouTube.

- Gosling, John (2009). Waging The War of the Worlds: A History of the 1938 Radio Broadcast and Resulting Panic. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4105-1.

- Holmsten, Brian; Lubertozzi, Alex, eds. (2001). The Complete War of the Worlds: Mars' Invasion of Earth from H.G. Wells to Orson Welles. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks MediaFusion. ISBN 1-570-71714-1.

- Schwartz, A. Brad (2015). Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles's War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-3161-0.

- The Martian Panic Sixty Years Later: What Have We Learned? from CSICOP

- The Martian Invasion at the Wayback Machine (archived July 21, 2011) describes instances of panic, outcry over the panic and the responses by the FCC and CBS

- BBC report on the 1926 Knox riot hoax

External links

[edit]- "The War of the Worlds" (October 30, 1938) on The Mercury Theatre on the Air (Indiana University Bloomington)

- Remastered MP3 & FLAC download from the Internet Archive

- The NPR broadcast of "The War of the Worlds 50th Anniversary Production" (October 30, 1988) from the Internet Archive

- War of the Worlds Invasion: The Complete War of the Worlds Website (John Gosling)

- mp3 of King Daevid MacKenzie's Echoes of a Century 2005 program which contains sections of the Chase & Sanborn and Mercury Theatre broadcasts of October 30, 1938, edited together in a manner approximating the sequence believed to have generated the reported panic

- The War of the Worlds – A Radio Program and A Film Score Archived September 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Who's Out There? NASA film with commentary on the 1938 broadcast and extraterrestrial life (1975)

- The War of the Worlds at Discogs (list of releases)

- Works by Orson Welles

- Mass psychogenic illness in the United States

- Scares

- Hoaxes in the United States

- American radio dramas

- CBS Radio programs

- 1930s American radio programs

- 1938 radio dramas

- American science fiction radio programs

- Works based on The War of the Worlds

- 1938 in the United States

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation–winning works

- Halloween fiction

- Radio programmes based on novels

- West Windsor, New Jersey

- October 1938 events

- Radio controversies

- New Jersey in fiction

- Live performances

- History of radio in the United Kingdom

- The Mercury Theatre on the Air

- Alex Rodriguez